How could Intel Capital, a world leading investment unit, have created more than $170bn in market value from investing in more than 1800 companies, and still not be able to steer its parent through market disruptions?

In 2018 Intel Capital, Intel’s storied venture arm, invested in Astera Labs, an AI chip company that went public in 2024 with a $5.5 billion valuation. The investment – and exit – highlighted the firm’s knack for spotting technologies that were “ahead of the curve,” says Pradeep Tagare, who served as Intel Capital’s investment director from 2003-2016.

But ICAP’s track record didn’t always translate into meaningful action at the corporate level, says Tagare, who currently heads up investments at National Grid Partners. The heart of the problem were structural and cultural disconnects between the venture unit and the rest of the company.

What was missing were the “mechanisms to get that knowledge back into the planning processes that a large company has.”

Pradeep Tagare

What was missing were the “mechanisms to get that knowledge back into the planning processes that a large company has,” Tagare says.

Today Intel has sunk into an existential crisis, torpedoed by an array of financial and technical challenges including the loss of lucrative AI chip market share to rivals like NVIDIA. Led by new CEO Lip-Bu Tan, the semiconductor giant is now shedding business units, slashing overhead costs and laying off thousands of employees. In an unprecedented deal to shore up the chipmaker, the Trump Administration last week injected nearly $9.9 billion in Intel, in exchange for a 10% equity stake.

The fate of Intel Capital itself is up in the air. In January Intel announced it would spin out the venture arm into an independent unit – only to have Tan reverse that decision in June, a few months after he took the reins from former CEO Pat Geisinger.

Amid Intel’s ongoing transformation, former Intel Capital managers shared insights on the venture unit’s strengths and successes, as well as challenges ICAP encountered internally and in its relationship with Intel. Known as much for its ecosystem approach to investing as its financial returns, the venture arm nevertheless struggled at times to integrate disruptive technologies gleaned from portfolio companies into Intel operations and strategy.

In the history of technology innovation, trying to identify a single factor that determines a given company’s success or failure remains a classic dilemma, Tagare observes. It’s also inherently difficult for investment of small equity stakes in startups to have impact on multi-billion-dollar businesses. That said, tighter linkages between the venture group and Intel’s business units, Tagare says, “probably would have led to better informed decisions” at the corporate level.

A winning strategy

A pioneering force in the world of corporate venture capital, Intel Capital was arguably a huge financial success, based on traditional venture returns as well as growth in Intel’s core chip business.

Since its formation in 1991 the venture arm has invested in over 1,800 companies, deployed more than $20 bn in capital and racked up more than 700 exits. In the past decade alone, the firm has created over $170bn in market value by investing in early-stage startups across key areas shaping the future of compute: silicon, frontier, devices and cloud.

ICAP in numbers:

- 1,800 companies invested in

- $20bn+ capital deployed

- 700+ portfolio company exits

- $170bn in market value created in the last decade

Beyond the financial returns, ICAP also generated tremendous value by growing new markets for Intel’s next-generation chip technologies. This so-called ecosystem approach was one of Intel Capital’s “most successful contribution,” says Lee Sessions, who led the unit’s portfolio business development and marketing teams from 2007-2017 and is now a course director at Global Corporate Venturing.

Probably the best-known example came in 2002, when the venture unit launched a $150 million initiative to support a wide variety of Wi-Fi startups. The initiative helped accelerate the rollout of nascent wireless technologies and drove demand for Intel chips capable of supporting Wi-Fi connectivity.

Among its investments were STSN, a provider of high-speed wired and wireless data communications for hotels and conference centers, and TeleSym, a developer of software for voice communications over wireless enterprise networks.

Intel Capital invested in startups focused on building out the middleware, software, and business models necessary for providing widespread Wi-Fi hot spots, which previously did not exist at such scale. This foundational work helped grow the Wi-Fi market, says Sessions, which in turn created new use cases for mobile computing, public hotspots, and smart devices—many of which relied on Intel processors.

The venture unit’s open source software strategy took a similar ecosystem approach, Tagare says.

“We invested in a bunch of companies that created alternatives to larger vendors – everything from application servers to data bases, up and down the technology stack,” he says. “That created alternatives for our customers to build upon the Intel platform as opposed to competing platforms.”

Balancing strategic vs financial priorities

The ecosystem model was a triple win – for Intel Capital, Intel’s core business and the startups, which were either acquired by other companies or had an IPO and became successful in their own right.

But like all CVC programs, Intel Capital had to grapple with changes in leadership and organisational priorities. The organisation that eventually became Intel Capital was started by Leslie Vadasz, one of Intel’s founding employees, notes Bryan Wolf, who served as ICAP managing director and vice president from 1997-2019.

“Les had gravitas within the corporation, so his leadership lent Intel Capital immediate credibility and importance within the company.”

Successive CEOs of Intel, from Andy Grove to Craig Barrett to Paul Ottelini, all came from the “same DNA” and understood the importance of the venture unit, says Wolf.

But subsequent leaders of Intel and Intel Capital had different perspectives, and in some cases less understanding of the venture model, which led to organisational changes that at times diluted the venture focus.

Wolf says there was a period of time when venture and corporate development were being performed by the same individuals, regardless of background, even though the skillsets of each discipline are in many ways unique. That decision was later reversed.

ICAP’s investment priorities also shifted depending upon who was leading the company and the economic environment at the time.

Starting around 2007 ICAP shifted from writing small cheques for companies with strategic merit to “writing large cheques for startups where the strategic value was not as strong.”

Pradeep Tagare

Starting around 2007, Tagare says, ICAP shifted from writing relatively small cheques for companies with strategic merit to “writing large cheques for startups where the strategic value was not as strong.”

A case in point were some of ICAP’s investments in Web 2.0 ecommerce platforms such as digital health and digital home technologies. “They provided some strategic benefit but not as strong as, say, the Wi-Fi ecosystem,” Tagare says.

Finding the right balance between strategic and financial returns is an evergreen challenge in the world of corporate venture capital, says Tagare. “Intel Capital had the same challenges.”

“Anytime you have that kind of change it creates a lot of uncertainty both internally and externally within entrepreneur and co-investor ecosystems.”

Siloed operations

Maintaining close connections with the parent company is another recurring issue for CVC programs. Throughout its 34-year history, ICAP struggled to integrate with Intel’s decision-making processes, former directors say. “It was always a challenge, to really have the business units digest what Intel Capital was uncovering in the ecosystem,” says Wolf, now a board member at Launch Oregon.

“Even when we were able to successfully bring new technologies, innovations, ideas, and potential disruptions from the market to Intel it was rare when the business unit would successfully take advantage of it.”

“Internally, Intel was somewhat disjointed and operated in silos. There wasn’t great coordination in successfully distilling key themes such as ‘the AI wave is coming.’”

Bryan Wolf

The structural disconnect extended well beyond the venture arm, Wolf says.

“Internally, Intel was somewhat disjointed and operated in silos,” he says. So while Intel received a lot of market intelligence through various avenues, Intel Capital included, “there wasn’t great coordination in bringing it together and successfully distilling key themes such as ‘the AI wave is coming.’”

Echoing those sentiments, Sessions notes that Intel Capital invested heavily in mobile phone- related technologies but – as has been well documented – Intel as a whole never really caught the mobile and smart phone wave.

“Some signals Intel would pick up on and do really well,” Sessions says. “Others maybe not so much.”

Unchartered territory

Even before the current crisis, Intel Capital had considered breaking away from Intel to become an independent fund. The venture arm is a balance sheet investor, says Sessions, leaving Intel Capital more vulnerable to belt tightening changing corporate priorities.

Given today’s dire circumstances – Intel recorded unprecedented losses of $19 billion last year – a spinout might have been the best option from Intel Capital’s point of view, he says.

“They may very well have said: ‘If we want to survive, we need to be separated from the balance sheet.’”

Instead, Intel will retain the venture unit, with an eye toward cost containment: In a recent statement, Bu Tan alluded to a possible fire sale of Intel Capital’s startup equity stakes and a retreat to investments that support Intel’s core manufacturing business.

“We wanted to work with the team to monetise our existing portfolio,” he said, “while being more selective on new investments that support the strategy we need to get our balance sheet healthy and start the process of deleveraging this year.”

Former executives say that, as an experienced venture capitalist, Tan would recognise the value of the portfolio and know that just one or two investments could pay provide a large payout.

“Given the current state of the company, leadership may be saying, ‘let’s monetise the portfolio and deploy the cash where we need it most’,” says Wolf.

Intel Capital holds lucrative stakes in several Chinese companies, as well as ASM, which makes photolithography machines to produce integrated circuits,

Like its corporate parent, Intel Capital is a pared down version of its former self. Intel Capital’s current website lists about 30 professionals (including investors) down from 42 employees listed in early 2024. Under Tan that downsizing could continue: Tan himself is a long time VC investor with a big rolodex of AI companies. He doesn’t necessarily need a large Intel Capital team to give him insights about the market.

On the other hand, Tan understands corporate venture better than most in the valley, says Sessions. “He understands that the hard work of corporate venture is really being able to integrate the world of venture with the world of what’s going on in that specific company.” Companies evolve as ecosystems evolve, Sessions adds, “and they live or die based on their ability to adapt.”

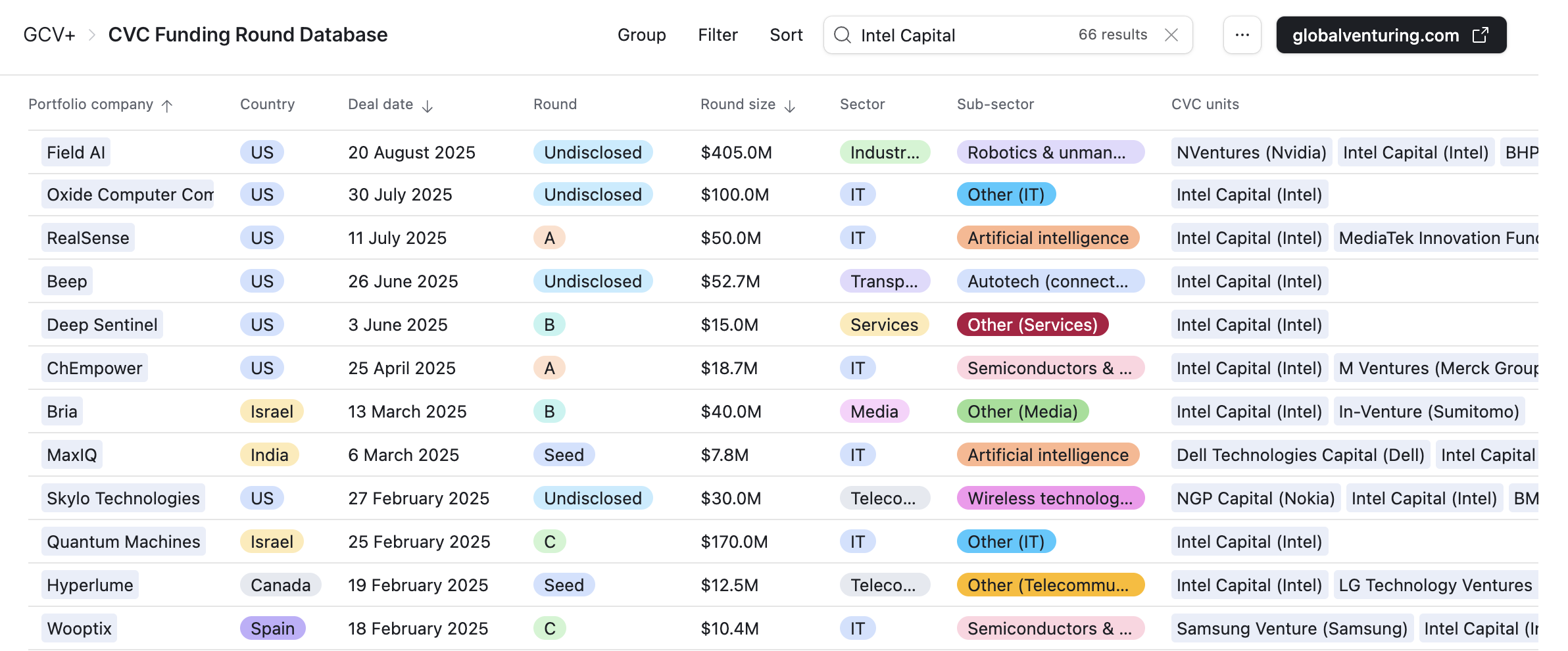

See all the recent startups backed by Intel Capital in the CVC Funding Round Database