Defence and industrial investors are increasingly interested in using quantum sensors to go where the GPS system cannot take us.

Much of the magic of modern life depends on GPS. It guides our flights to the right destination, ensures our orders are shipped correctly, and rescues the directionally challenged among us with that invaluable blue dot on our mobile phones. In short: we are hopelessly over-reliant.

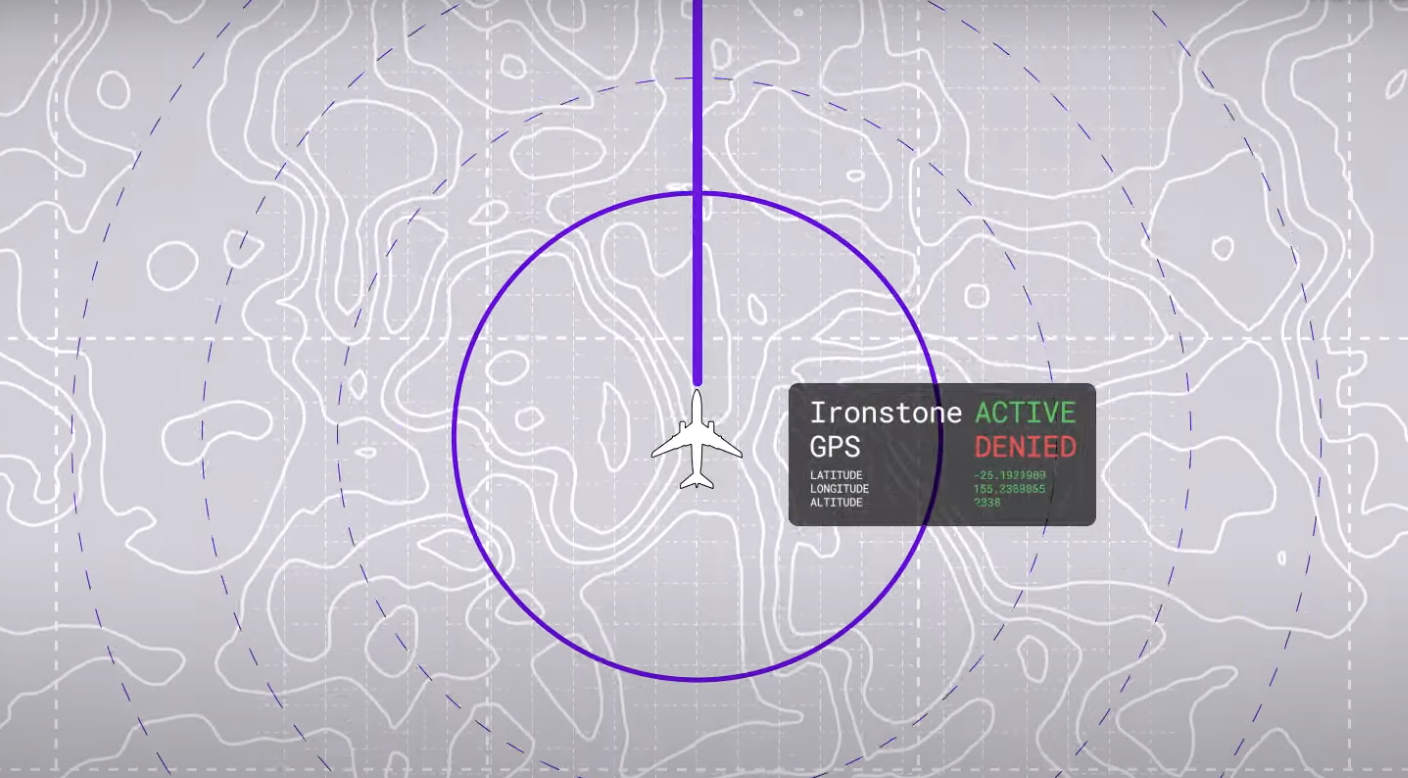

For an idea of why this could be dangerous, you only need to look at Ukraine. Since Russia’s full-scale invasion, GPS denial has become a weapon on the battlefield, cutting off aircraft and drones from their positioning systems. In fact, spamming and spoofing has started to creep outwards into other eastern European countries and the Baltic States, as this map shows. It is so integral to the modern economy that an outage could cost the US $1bn a day, according to a Commerce Department estimate.

This has fed an interest in alternative technologies. One of the most promising of these is quantum sensing, where the peculiar properties of subatomic particles allow for a highly sensitive reading of gravity, which is used to measure speed, position and orientation — a considerably more sophisticated form of the technology that helps position a smartphone. Successful innovators in this sector could tap into a substantial market. A 2021 McKinsey report predicted that quantum sensing will generate $5bn in revenue by 2030 across several use cases, including navigation.

“Everything has become so dependent on GPS, and the assumption is that it is simply [always] available,” says Michael Biercuk, CEO of Australian startup Q-Ctrl, which has raised $113m and built a quantum sensing-based navigation system which it claims is over 100 times better than the next-best GPS alternatives.

The Ironstone Opal system uses an on-board sensor that detects miniscule changes in magnetic fields and then plots the vehicle’s position against a map of the Earth’s magnetic field using AI-powered software.

Deep tech startups like this can often struggle to move from prototype to scaled product, but Q-Ctrl is using strategic relationships with corporations to bridge this gap. It has partnered with US defence giant Lockheed Martin on several US Department of Defence contracts to make prototype quantum navigation systems based on quantum gravimetry and inertial sensing.

Biercuk says that working with a strategic investor like Lockheed Martin Ventures is a “strong foundation” for deploying at scale in the defence industry.

“The partnership massively enhances our access and speed of execution with the [US Department of Defence],” says Biercuk.

“It’s not like we just have to figure it out from a blank piece of paper, and it’s been proven by how rapidly we have attracted large contracts. For future scaling in the defense sector, that access is essential – it’s extremely hard to break in from nothing.”

Besides airborne navigation, quantum sensing could also be used in underground mapping, where GPS could not penetrate anyway. Beneath the Earth’s surface, gravity readings can reveal the geological layout, identify tunnels or cavities, and position vehicles like trains.

In the UK, a spinout from the University of Birmingham, Delta.g, is making a sensor designed for underground exploration. It works by firing a laser at an inert atom to detect shifts in gravity that can build a detailed picture. Katy Alexander, chief marketing officer, says the company’s aim is to be a “Google Maps for the subsurface”. A quantum sensor could help mining companies produce detailed surveys to cut down on unnecessary drilling, or be used in construction to detect underground pipes or other potential obstacles.

The method, gravitational gradiometry, is not new, but Alexander says conventional methods suffer from a sensitivity to noise and other limitations which quantum sensing avoids.

How corporate partners are helping quantum sensors to scale

Like all deep tech areas, the capital needed to get experimental technology off the ground is immense, and sensing does not draw the same kind of investor interest as quantum computing, its distant cousin.

Alexander argues that the UK is “punching above its weight” in quantum sensing technology, but that the sector suffers from poor funding. She thinks a more active pro-quantum stance by the government is a step in the right direction, however. The Industrial Strategy policy paper published in June makes reference to supporting “frontier industries” by developing cutting-edge technology areas, including quantum.

“What’s exciting with quantum sensing is that we’re looking at a technology far closer to market readiness than quantum computing, with the potential for enormous near and long-term impact,” Alexander says.

“So much IP has come out of the UK, but where we’ve consistently fallen short is in the commercialisation stage. With the new UK Industrial Strategy and the European Quantum Strategy placing greater emphasis on quantum deployment, we have a real opportunity to change that.”

And while the example of Q-Ctrl working with Lockheed Martin shows how corporate partnerships can be beneficial, that’s not the only way large companies are helping to bring the technology to market.

The German technology giant Bosch demonstrates how venture building can help commercialise the technology. In 2022, it developed an in-house venture called Bosch Quantum Sensing, drawing on the company’s R&D expertise. In April, the startup entered into a joint venture with Element Six, which makes synthetic diamonds, a material that can be used in quantum sensors.

Bosch Quantum Sensing previously teamed up with Airbus to explore its applications for commercial navigation. Q-Ctrl is doing something similar, having also received investment from Airbus Ventures.

These networks of partnerships could hold lessons for other deep tech sectors looking for ways to make the leap to commercialising products.