The new wave of agtech startups are more savvy, more grounded and more niche than the hyped companies of previous years. It's "a great time to invest", say corporate VCs.

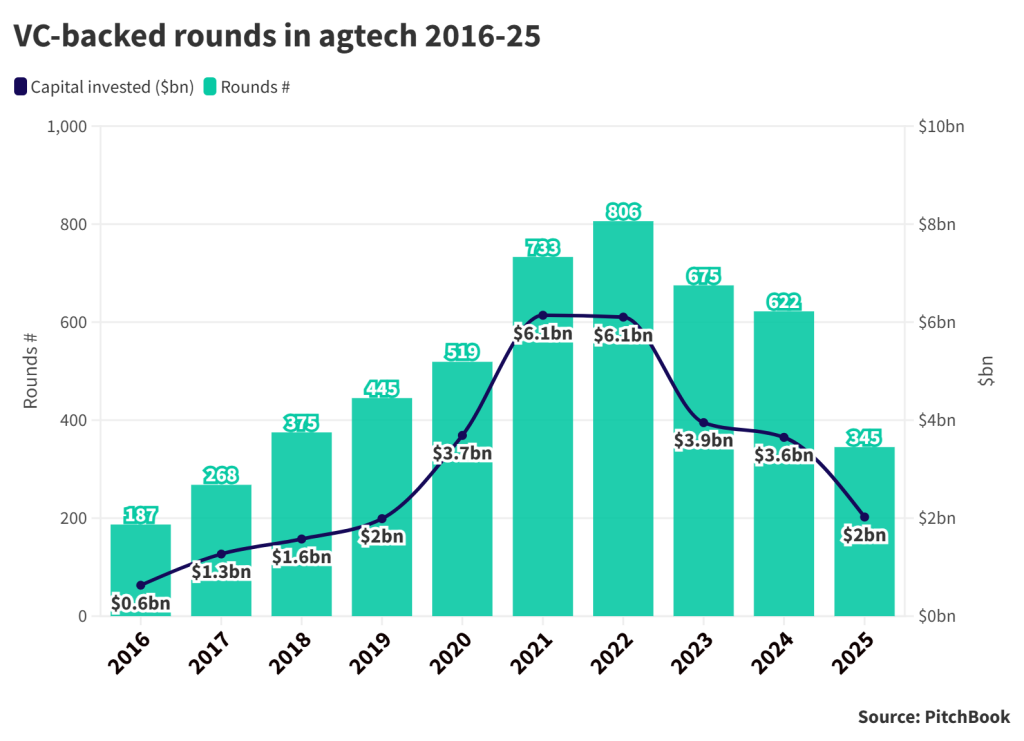

Funding for agricultural technology has been steadily trending downward, with 2025 set to be the leanest year this decade. But corporate investors at the World Agri-Tech Summit in London this year are cautiously optimistic that the sector is finding its way out.

“If you look at the numbers, this year has one of the lowest investment amounts since 2015,” says Xin Ma, chief investment officer for dairy producer Fonterra’s Ki Tua Fund. Mainstream venture capital and sovereign wealth funds had entered the sector en masse in the last VC boom, only to pull back when they found agtech’s longer product development times couldn’t provide quick returns.

But now, she says, a new set of companies are emerging with strong fundamentals and attractive valuations.

“Although it is seemingly challenging, it’s actually a great time to invest,” Ma says. “Companies are more grounded, and they have started to really focus on delivering. I really think it’s actually a good vintage now.”

That more grounded approach is also a reflection that some of the more expensive areas of agtech, like indoor farming or meat alternatives, have thinned out. Companies in the sector are no longer closing large series B and C rounds without any route to profit.

“The truly speculative stuff that I think was a problem in 2022 and 2023 is gone,” says Shubhang Shankar, managing director at agribusiness Syngenta’s corporate venture arm.

“What I see is that there are more credible companies left, and I hear them say, ‘Yep, we’ve been plugging away silently, not raising huge rounds, but have built a commercial business, or got customer traction’.”

Another factor is that this newer wave of startups have more expertise when it comes to the nuts and bolts of farming.

“I think what we’re seeing now is what I would call the second generation of agtech,” says Albena Todorova, venture partner at agriculture-focused bank Rabobank’s venture arm, Rabo Ventures.

“The specifics of that second generation are that founders are more agriculture savvy, or at least they are smart enough to bring in someone who understands agriculture as well. It’s not just someone who wrote an algorithm and has made a dashboard that collects data from a bunch of sources and is walking around trying to sell that.”

AI is a factor in hardware, but software is still looking for a big use case

A key area of agtech remains seed optimisation – the largest agtech VC round this year was closed by seed design startup Inari – but the other notable segment is robotics, where artificial intelligence technology is being used to enhance farming equipment.

“I see a lot of things which are driven at the intersection of machinery and software,” Shankar says. “I think that, by some distance, that seems to be an area where there is customer demand and customer willingness to explore technology and innovation solutions.”

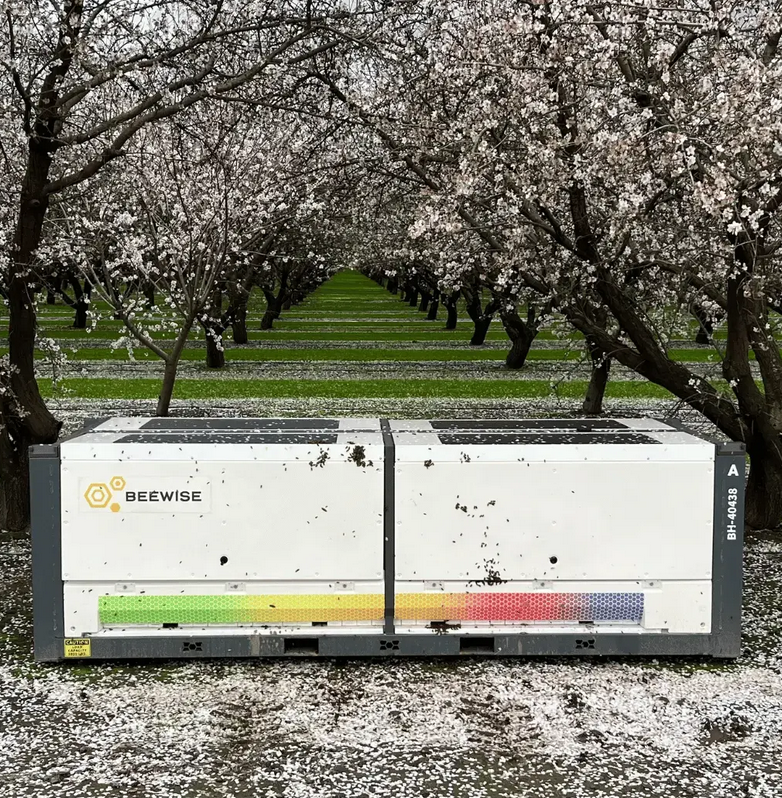

That can also be seen in the stats. Crop monitoring system developer Soflintec, automated electronic beehive provider Beewise and BinSentry, creator of an AI sensor-equipped feed monitoring device, are among the very few agtech companies to raise $50m or more this year. But pure-play AI software products have been less successful with farmers.

“If you are a pure software-only business – and I think this is now well established in our industry – it’s hard to scale and it’s hard to get customers’ acceptance,” Shankar says. “They’re not looking for a new software or artificial intelligence-driven offering that completely changes what they’re doing on the farm.”

Another issue facing AI systems is their reliance on data, which is far more difficult to accurately collect and quantify on a farm than it is with, say, an online store.

“A lot of the AI solutions are built for conversational models and based on publicly available data,” says Todorova. “How much publicly available data is there about farmers’ operations for instance?”

That process is made even more complicated by some of the vast differences between farms, she adds. It’s very difficult to come up with an AI product that can work for both a Polish potato grower with 100 hectares under management and a 10,000-acre potato grower in the US or China.

Ma suggests AI could make a substantial difference in bioscience, accelerating the identification of genetic strains in seeds, in much the same way the life sciences industry is increasingly using it in drug discovery. But perhaps its greatest potential use case in agtech is within the supply chain, which more or less everyone agrees can be made more efficient.

“One of the big promises in AI is actually not in the in-field production, it’s everything post-harvest. I think that’s an interesting space,” says Todorova.

Fresh produce can change hands some six or seven times in the supply chain once you take finance, storage, logistics and quality assurance into account, she adds. The key would be to shorten that without sacrificing quality. And although various founders have tried to apply blockchain and AI to solving that, no one has yet succeeded.

Startups are targeting customers more precisely to build sustainable businesses

Perhaps because there is less money flowing into the sector, the agtech startups which are emerging tend to be in more niche areas rather than aiming for an all-encompassing solution for everyone.

“I think people are now designing for niches and for the markets as they exist, rather than throwing technology at a problem and seeing what sticks,” says Shankar.

That also means that even parts of the market which have swung wildly out of fashion can be viable if you know where to look.

Food and beverage group Paulig’s agrifood investment arm, PINC, has emerged as one of the sector’s most active investors, with three deals in the past four months. While some of those startups are in very unfashionable areas, they have business models linked to specific price-based demand.

BlueRedGold’s indoor farming operation focuses not on leafy greens but premium saffron, which is used in medicines and cosmetics and which can retail for thousands of dollars per kilogram. Win-Win is using fermentation to make cocoa-free chocolate that is not only more ethical, but which is going to look more and more affordable if cocoa and cacao prices continue to rise due to climate change.

“You’ve seen all the price developments in both cacao and coffee,” says Marika King, head of PINC. “Sometimes, people think inflation in the stores or food prices comes from one thing… but it’s a lot about all these climate pressures we have on our farmers…it’s hard to grow food when crops get slaughtered by drought or by too much rain.”

PINC believes the key is not size but profitability, targeting technologies that can enhance things in small ways.

“Sometimes, when we don’t know what the winner is going to be in a particular field, we try to find the enabler that pushes the whole field up a little bit,” says King. An example of that would be Elaniti, a British startup PINC backed at seed stage this year. It uses data science technology to map and analyse soil to help farmers make decisions in areas like what kind of fertilisers to use.

Shankar believes a niche approach can still find enough users, and cites the founder of a smart weeding robot startup he recently spoke to. The company can’t serve the needs of a corn or soy farmer, but it isn’t targeting them. The product has been designed specifically for crops like carrots or beetroots, grown by farmers who are phasing out chemicals.

“It’s absolutely fair to say that perhaps you will not build the next Tesla or OpenAI with that approach, but you don’t have to. I think you can build a very viable and credible business with that approach, a self-sustaining $20m, $50m, $100m business. And maybe that’s what the future of agtech is: 50 companies with revenues between $50m and $100m, rather than five companies with $10bn in revenue,” he adds.

“So, I think we’re at the end of this creative destructive cycle. One end of the destructive cycle is over, but now the creative cycle is in, and I think the survivors are people who have viable businesses. Will they succeed? Will they become big? Who knows, but I do see that change.”