A large number of new CVC units have been set up in the past few years. How will these newcomers weather the coming downturn?

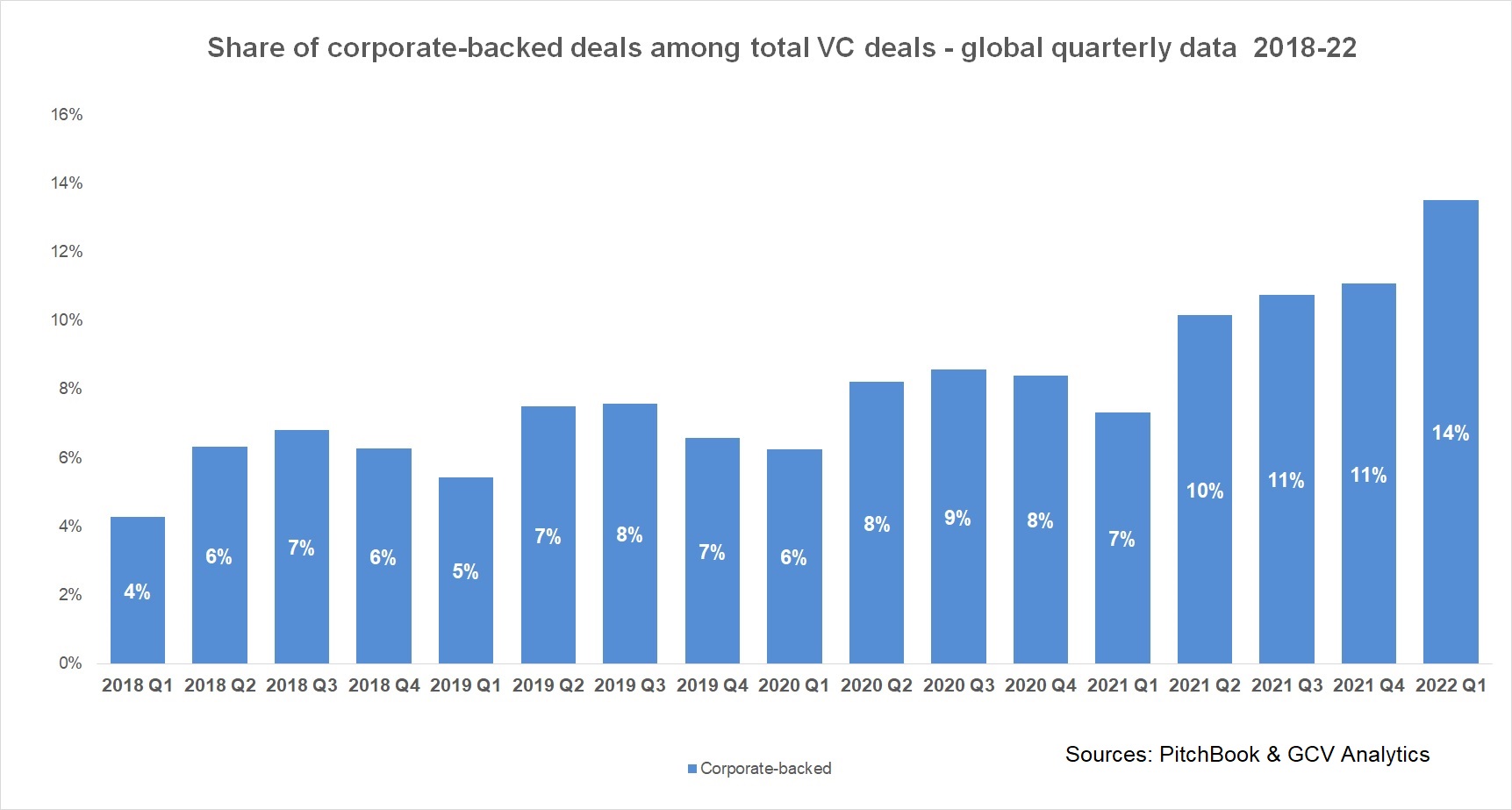

Corporate venture capital has never been so buoyant. In the first quarter of 2022 we saw more than 1,500 corporate-backed deals, worth an estimated total of $69.6bn – higher than in any other first quarter on record so far. In fact, CVC investing has been more buoyant than the total VC market and accounted for 14% of deals in the first quarter.

Furthermore, the majority of the corporate investors who did a deal in 2021 have already returned to do one in Q1, implying that either there is still momentum in deal making or that corporate investors have enough dry powder to sustain this activity, at least for the moment. And we are seeing more corporations making their first-ever venture capital investment into a startup.

However, the nagging question is: how realistic is it to expect this to continue?

Tough times ahead

Every indicator suggests tough times ahead. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has shocked a world still trying to shake off the disruption of the pandemic. Supply chain disruptions caused by the pandemic have yet to be completely resolved, while a raw materials crunch has sent the prices of soft and hard commodities skyrocketing. All of this has greatly contributed to exacerbating inflation rates across much of the developed world. The Federal Reserve of the United States and other central banks across the globe have in response already begun tapering and hiking interest rates in a push to tackle high inflation. And while much of the world is trying to put the pandemic behind, a considerable part of East Asia is still either under strict lockdowns like China or with significant border restrictions like Japan.

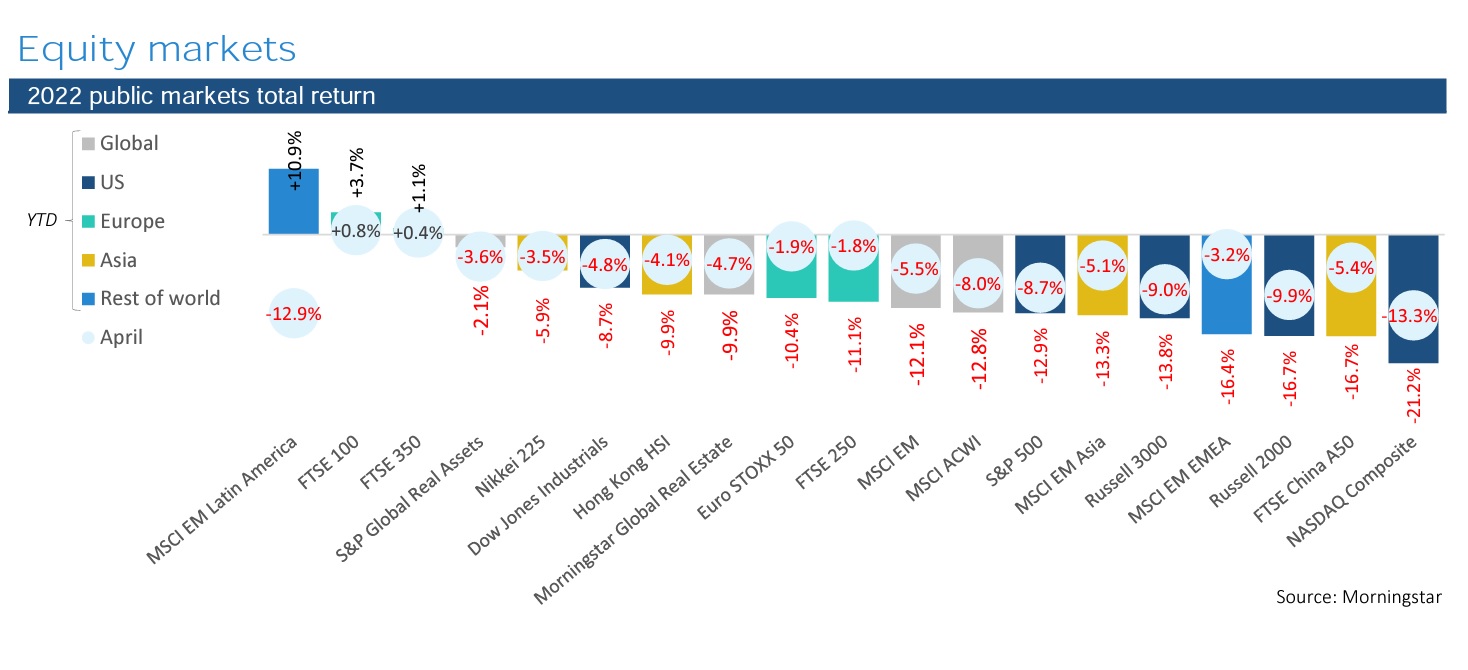

Markets have already reacted to all of these. Particularly pronounced has been the reaction of liquid and actively traded markets. Not only have major US indexes like the S&P500 and Nasdaq 1000 slumped this year but so have other major stock indexes around the world, as shown on this graph by PitchBook and Morningstar.

M&A markets have also reacted and weakened in response. According to PitchBook´s latest report on M&A activity, the impact of global and macroeconomic factors has been palpable in Q1 2022 and likely to become even more evident in total figures going forward. According to the report, a fallout from the invasion of Ukraine forced banks to hold tens of billions in loans used to finance leveraged buyouts (LBOs). This has caused PE firms to turn to private debt providers to finance deals, further taking market share from the big banks. A sceptic might wonder if this was truly caused by general uncertainty from the war in Ukraine or general uncertainty about the next rate hike of the Fed, which stood at 0.5% and was eventually announced in the beginning of May.

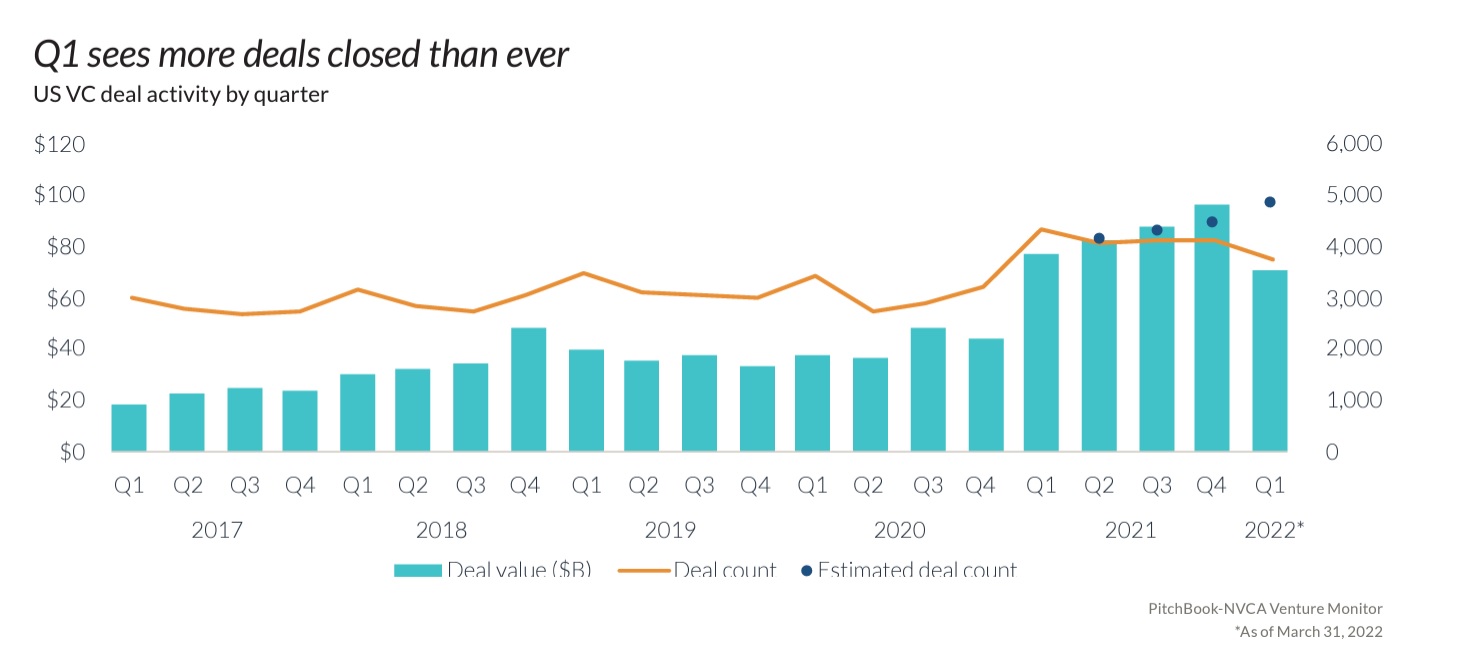

Venture capital has been slower to react. According to the latest quarterly monitor report by PitchBook and the NVCA, the US venture capital market remained still vibrant during the first quarter of 2022, registering more deals closed than in any other first quarter, before or after the pandemic.

However, the tone of the report is diplomatically cautious, noting that “the start of 2022 suggests the onset of an imminent but healthy recalibration period”. And, although Q1 was a strong quarter, the number of closed deals was lower than in the last two quarters of 2021.

Which brings us back to the question: how long can corporate venture capital seemingly defy gravity? Probably not very long, although not every sector is likely to be hit to the same extent.

Reacting slower than VC

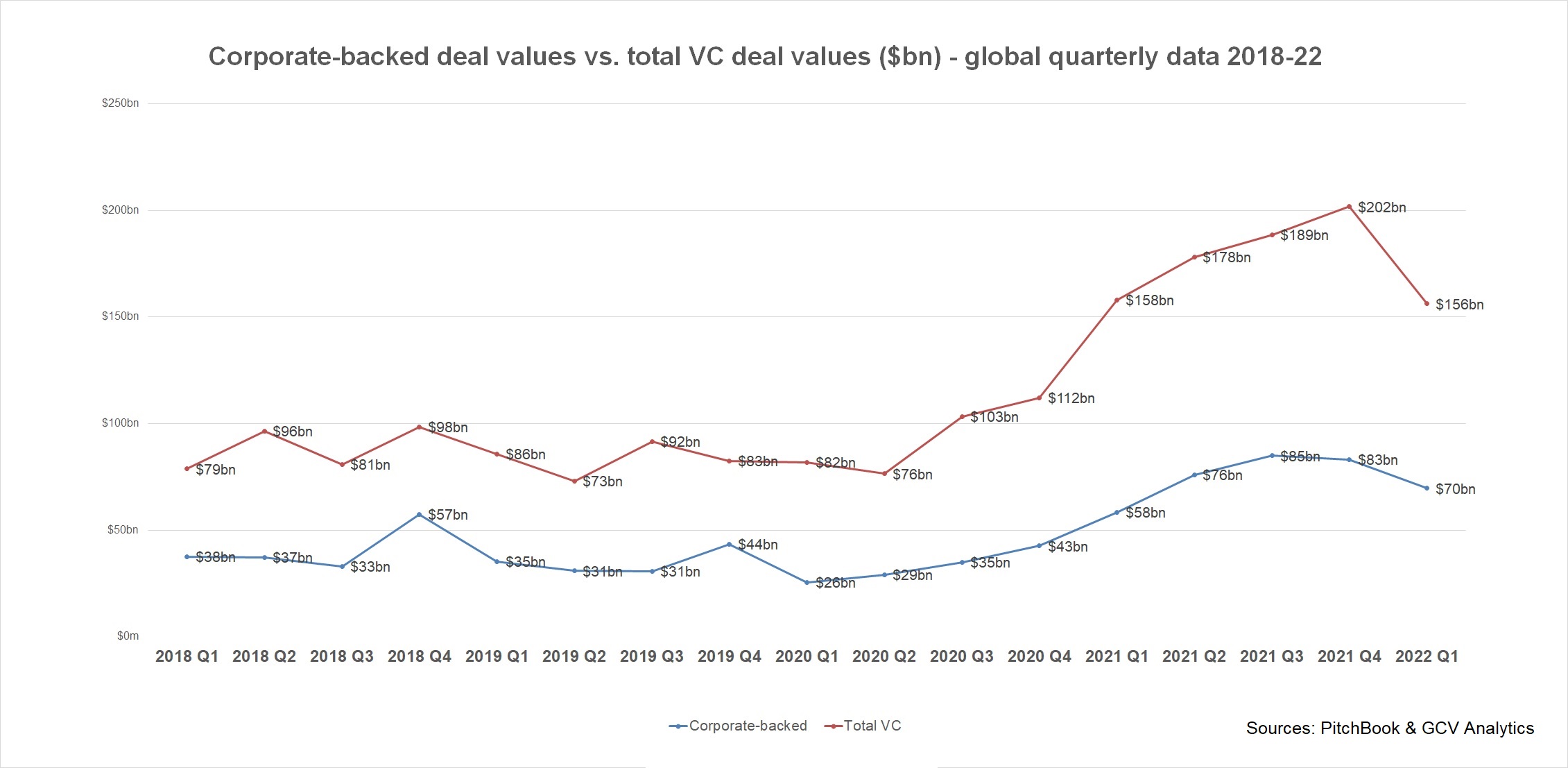

Traditional VC firms have started reacting to the market downturn faster than CVC investors, especially if we look at the total estimated dollar figures. Downward pressure on valuations would translate into fewer large-size deals, which would imply a noticeable correction in total estimated dollar figures. That indeed has happened in the case of total venture capital figures globally.

According to PitchBook´s data, the total estimated dollar value of global VC deals in the first quarter stood at $156bn, roughly comparable with Q1 of 2021 but sharply down (-23%) from the Q4 figure ($202bn).

In contrast, the total estimated capital in corporate-backed rounds globally was $70bn, 20% higher than the $58bn in Q1 2021, and 16% lower the $83bn in the last quarter of last year. If anything, corporates have tended to participate in more of the large-sized deals. They are slowing down dealmaking like the rest of VC investors but not as swiftly. All of this is in the context of corporate-backed deals already forming a noticeable part of the total VC dealflow, having increased over the past few years from 5-6% to well over 10%.

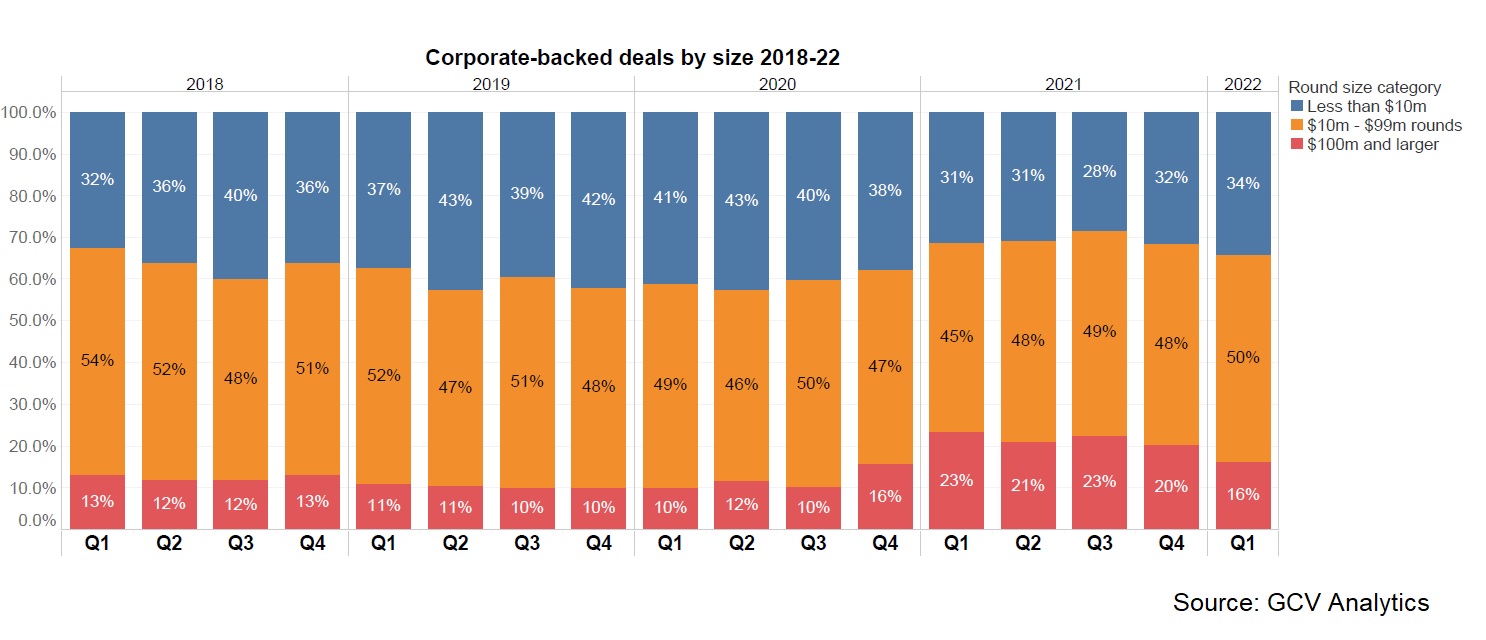

Does that mean that corporates are participating in more large deals with bloated valuations? Not necessarily. Throughout 2021, large deals sized $100m and above constituted well over 20% of all corporate-backed deals, according to our estimates. In Q1 this year, this statistic has started coming down to 16% and we eventually expect it to reach its normal historical range of around 10-12%, assuming both downward pressure on valuations (which may be yet to appear) in addition to cautiousness on part of investors.

Novice CVCs beware

One indicator of concern is that that there are a lot of first-time corporate investors that appear to be dipping their toes in minority stake investing at the moment. An estimated 17% of corporates that made an investment in Q1 did so for the first time — although we should note that there may be some limitations to our data here as some companies may have done small deals before without much publicity. However, taken together with numbers from 2021 — in the third quarter last year nearly a quarter of corporate investors were first-timers — we can see a clear trend of novice corporate investors coming into the market

Though there is certainly nothing wrong with stepping on the venture investing scene, the risk lies in the lack of experience of such newcomers. They have simply not lived through a harsh economic downturn.

Cyclical vs non-cyclical investments

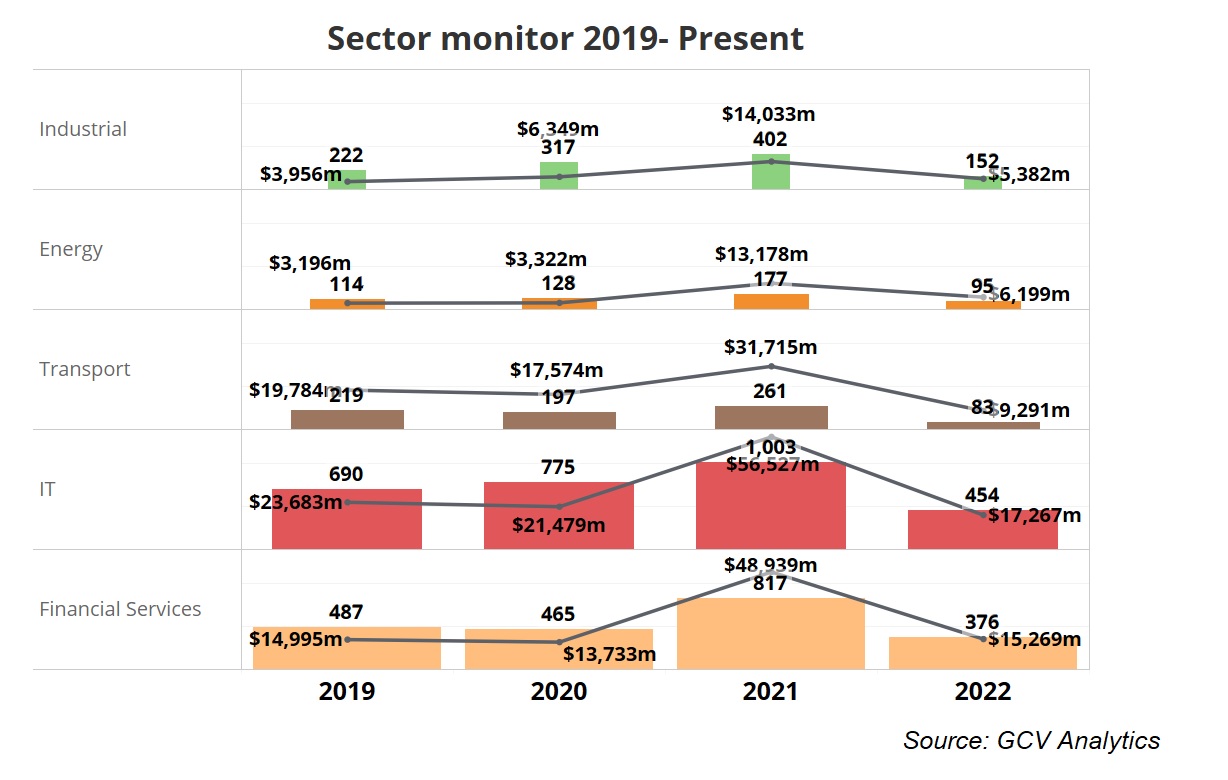

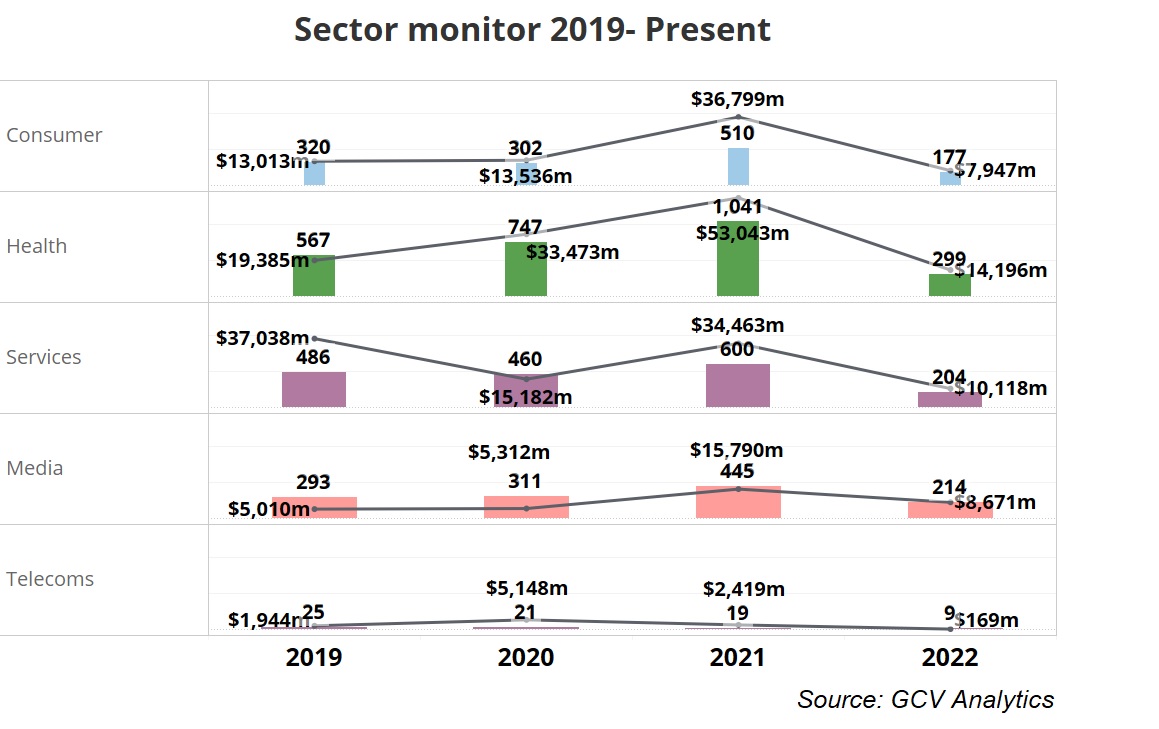

If we are heading for a downturn, how will the pattern of corporate investments be affected? Corporates have invested roughly equally in cyclical as well as non-cyclical or countercyclical emerging businesses. So far corporate-backed deals in emerging businesses from nearly all sectors have largely held up this year in numbers but is this likely to continue with a shifting economic paradigm? According to our data, there does not seem to be a slowdown in corporate investment across startups from different sectors, as illustrated on the next two charts below. It is reasonable to assume that corporate investments, on a net basis, have been evenly spread among cyclical and non-cyclical areas.

If stock markets are to be considered a good proxy for overall economic expectations, nearly every sector except energy and utilities has been battered since the beginning of the year. Data from our latest Energy Council quarterly report, corroborate this bullish trend for energy. This is not only due to rising oil, gas and other commodity prices at the moment but also in the context of a global energy transition to net zero.

What markets seem to discount, however, is 1970s-style stagflation, a period with little to no growth and high inflation, fuelled by a supercycle upmove in commodity prices. On top of this, we may need to also consider the possibility of rising interest rates, as even with recent hikes, they are still very low, historically speaking.

If these fears materialise, most sectors would see an impact with some being much more vulnerable than others, sometimes irrespective of their cyclicality. More resilient sectors include life sciences and pharmaceuticals (though rising interest rate may considerably change the way drug development is financed today) as well as consumer staple categories like foodtech (and agtech, correspondingly). Certain cyclical areas may also remain relatively robust, like real estate and proptech, non-speculative fintech (e.g. insurtech and banking) as well as most horizontals and verticals related to energy and raw materials.

Areas that may end up being more vulnerable to economic adversity may include speculative growth deeptech and IT applications, consumer discretionary products and servicers (anything from automobiles through e-commerce and consumer electronics to travel tech) and some more cyclical industrial businesses that may not be able to shift rising raw material costs completely onto consumers. In that list, we may also need to consider other areas like entertainment and media (gaming, virtual reality and mixed reality, metaverse etc.) as well as speculative fintech (e.g. crypto assets).

Weathering the downturn

How much would a downturn strain corporations? History suggests the effects could be brutal. London Business School professor Gary Dushnitsky noted in the Collier Institute of Venture’s 2015 history issue that a previous golden age of corporate venturing from the 1960s, when around 25% of Fortune 500 companies ran CVC programmes, was brought to an abrupt halt by the 1973 oil shock and the collapse in the market for IPOs. Almost all programmes were terminated.

The new CVCs that entered the market in the past 2 years are likely to face a steep learning curve, fighting for their survival, funding and portfolios. This would follow the natural logic of a stagflationary period, where lower growth and profits would mean reduced budgets for innovation initiatives and reduced funds for venturing in the corporate world.

Abrupt or poorly handled exits from venturing could, however, result in long-lasting reputational damage for corporate venture investors. Not too long ago, the remnants of such reputational damage from decades earlier in the industry were still out there and one could hear comments pejoratively describing corporate venture investors as the “dumb money”.

On the bright side, downturns since the 1970s have been different. The 2008 financial crisis led to a larger number of CVC launches than ever before. There was a shorter-lived commodities supercycle from 2000 to around 2010-2011, which did not cause as much damage to the world of innovation as the one in 1970s, with the dot-com bubble, 9/11 and the global financial crisis all in between.

In either case, heads of CVC units will have to be at the top of their game, demonstrating both the strategic and financial value of their investments to the c-suite and corporate shareholders. Global corporate venturing aims to to address this risk by providing the community with events and conferences to find the right partners and build the right investment network. We are also aware of the need to professionalise and train the industry. This is why we have set up the GCV Institute, offering a variety of courses for professional development within the realm of corporate venture capital, ranging from basic to advanced.