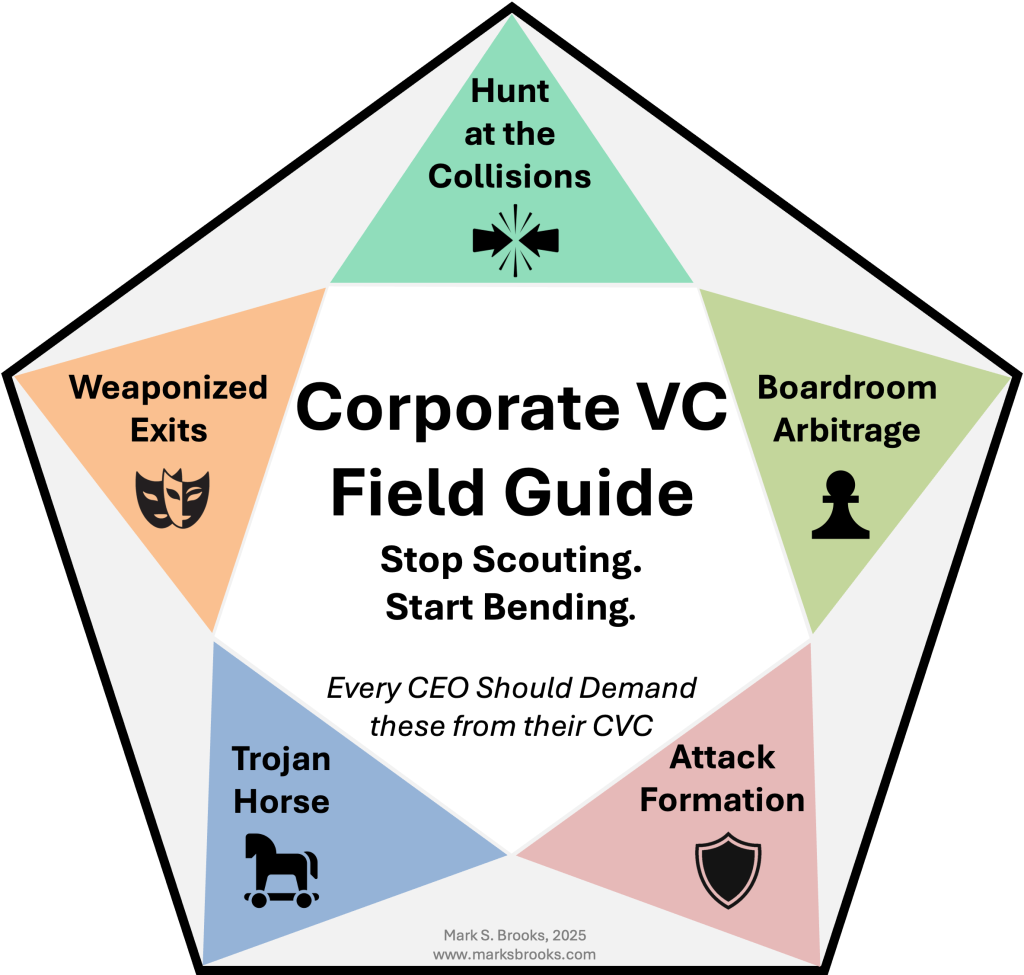

Too many companies are just scouting for innovation when they should be investing to build networks, influence markets and destabilise competitors.

Corporate venture capital is sitting on far more power than it currently uses. Only 52% of corporates who invested in startups in 2023 returned to make further investments in 2024, according to the latest GCV data and nearly a quarter of CVC funds don’t reserve any capital for follow-on rounds. For a large proportion of corporate investors, backing a startup is a one-and-done exercise. Programs look active, but activity does not equal influence and it rarely bends markets.

Yet corporates are still on the field when others retreat. While overall venture investment volume fell 17% in 2024, corporate-backed startup funding rounds increased by 4%. The number of dollars raised in corporate-backed rounds increased 20%. The staying power is there. The question is what to do with it.

Showing up isn’t enough. Too many CVCs still operate like scouting units – funding startups, passively attending board meetings, waiting for insight to trickle back. Meanwhile, capital, talent, and customers are flowing elsewhere.

It doesn’t have to be this way. CVCs can bend markets. They can reshape flows of capital, customers, standards, and talent in ways that tilt advantage toward their corporate parent.

A previous piece, The end of corporate venture capital as we know it, argued that CVCs must be elevated to the CEO and Board level, and laid out the STRATEGIC framework for building programs with staying power. That brings us to this field guide: five specific plays that turn corporate venture capital into a market-bending force.

The five plays

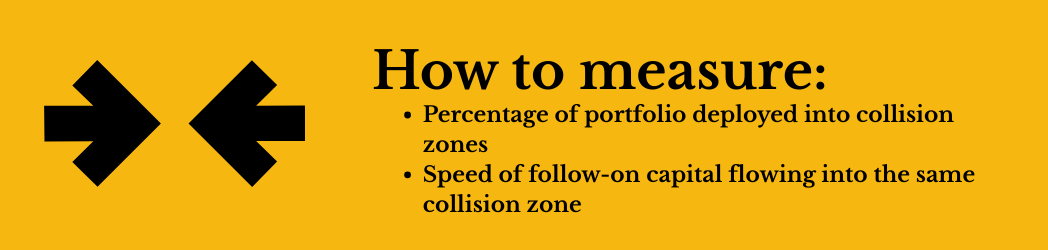

Play 1: Hunt at the collisions

Inside mature industry verticals, the rules are already written, moats defended, incumbents coordinated, and regulatory pathways well worn. Innovation there is incremental at best.

The future gets built where categories collide. At these seams, buyer budgets straddle functions, economics aren’t priced in, regulation is unsettled, and incumbents are uncoordinated. Think of carbon credits colliding with agricultural inputs, where farmers, food companies, and financial institutions all stake budget claims in traceability solutions. Or the convergence of mobility and energy, where EV charging straddles utilities, real estate, and automotive OEMs. Or the overlap of healthcare and consumer tech, where continuous glucose monitors and wearables blur the line between medical devices, lifestyle gadgets, and nutrition. These are spaces where pricing power and category rules remain unwritten and where new models can win.

CVCs can pull corporates into these collision zones, investing where the next categories will be written – often before we even have names for them – and certainly before competitors realize the game is changing. This matters because every corporate has a limited shelf life if it stagnates in the same space for too long.

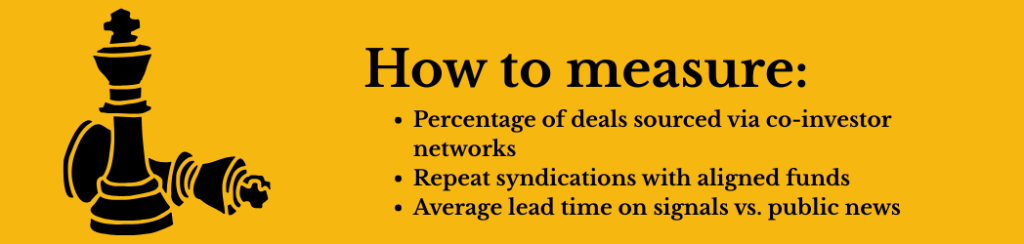

Play 2: Boardroom arbitrage

Most CVCs treat co-investors as acquaintances. But every board seat is a window into another fund’s dealflow, theses, and blind spots. Ignoring this is leaving leverage on the table.

Market-bending CVCs turn co-investors into a meta-portfolio and intelligence engine. They map syndicate partners’ theses, track overlaps and adjacencies, and deliberately trade pipeline deals. Over time, this creates preferential access to companies that might never have crossed the corporate’s radar. Think of it as an insider Bloomberg terminal for the next economy, or a way to see shifts months before the press or bankers do.

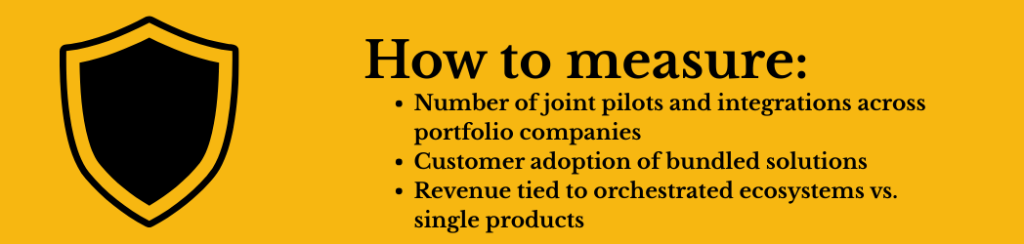

Play 3: The attack formation

Don’t just back point solutions. Build an attack formation around a problem the corporate wants to solve.

For example, a cardiovascular health strategy could mean investing in sensors, therapeutics, devices, and foodtech. Some assets might eventually be rolled up into one platform; others orchestrated as a de facto ecosystem. In agriculture, an inputs company chasing traceability might back DNA-tagged chemistries, supply-chain visibility platforms, and analytics startups that knit them together.

In both examples, the corporate isn’t betting on a single winner. It’s creating a diversified, de-risked coalition, and positioning itself as the orchestrator when the problem is solved.

Play 4: The Trojan Horse entry

Some markets can’t be entered directly because they are too regulated, too political, or too hostile to an incumbent brand. That’s where portfolio companies become Trojan Horses.

A startup can establish a presence where the corporate can’t such as an emerging geography, a sensitive category, or a new distribution channel. The CVC provides quiet backing, commercial introductions, and market intelligence, while the startup secures a beachhead.

For example, a mobility corporate backing a neutral EV charging startup can gain early access to municipalities that would resist direct corporate entry. Later, the corporate expands through partnerships, acquisitions, or infrastructure tie-ins enabled by the startup that cleared the path. In this hypothetical example, CVCs that use startups to wedge into this space – like tightening EV network integration – can position their corporate parent ahead of the infrastructure curve.

Play 5: Weaponised exits

Exits are more than liquidity events. They are a special kind of choreography.

A corporate can sell to an ally to entrench its lane. It can merge two portfolio assets early to consolidate a fragmented space. Or it can sell to a competitor, especially when there’s high confidence the technology won’t scale. The rival burns capital, time, and management focus, while the corporate reallocates resources to the real prize.

For example, Google acquired Nest in 2014 for $3.2 billion. Incumbents (Honeywell, Johnson Controls) scrambled to defend their smart-home positions, burning capital and focus, while Google quietly integrated Nest and set itself as the default.

Even an early or breakeven exit can be worth it if it tilts the market. In strategic warfare, sometimes the most valuable move is handing your opponent the weapon that doesn’t fire straight.

Momentum as a force multiplier

Momentum makes every other play hit harder. It positions your bets as the early category-definers (play 1); compels partners to double down, bringing you better deals (play 2); wins strung together become a campaign, not scattershot bets (play 3); a wedge amplified by visible traction looks like the whole beachhead (play 4); a sale framed as part of the narrative tilts the perception of inevitability (play 5).

Momentum turns one win into fuel for the others. You land one statement-making win, stack supporting cases, anchor with a trend metric and the market starts chasing you. Just look at Tesla: early customer and media momentum didn’t just grow its share, it made the market assume Tesla would define the future of EVs long before production caught up. Tesla’s early customer momentum forced incumbents to chase its story long before the technology was proven at scale.

The challenge

Without a mandate, a venture arm is an expensive scout. With it however, the CVC becomes a lever that rewires the market. That’s why part 1 argues that a CEO-level mandate and board commitment are required for any of this to work.

Master even two of these plays and you’ll change your category’s trajectory. Master all five, and you will do more than participate in markets – you’ll write the rules others will be forced to follow before they even know the game has changed.

Mark S. Brooks is a former academic scientist, entrepreneur, corporate executive, and CVC leader who built and scaled programs at FMC and Syngenta, deploying $75m+ across ag/bio/climate and catalyzing $250m+ in follow-ons with seven exits. He is now seeking his next executive mandate: orchestrating investment, partnerships, and strategy in ways that bend markets. He can be reached at hello@marksbrooks.com