A small but growing number of CVCs are quietly reaching fund sizes of more than $1bn. When they get there, life changes in some ways.

A billion dollars has a totemic significance in venture capital. Investors chase after companies with potential to reach the billion-dollar unicorn valuation. But what about when they themselves become unicorns, with more than a billion dollars to deploy?

Most corporate venture units start much smaller than that, sometimes with just a $50m allocation or $100m. If they are successful, they gradually add to this with new, slightly larger funds and if they keep going long enough, some can reach the $1bn mark, either in capital committed or in assets under management.

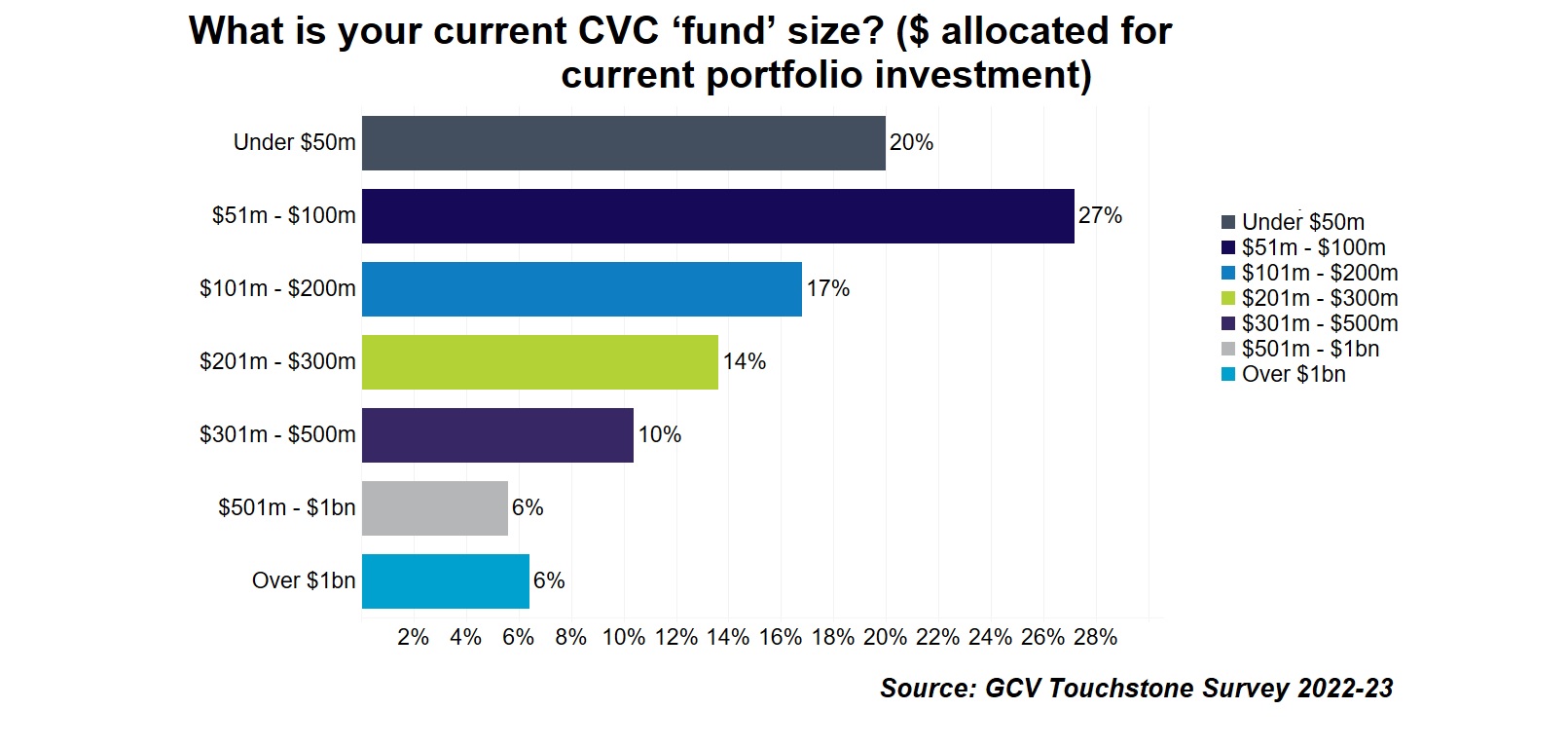

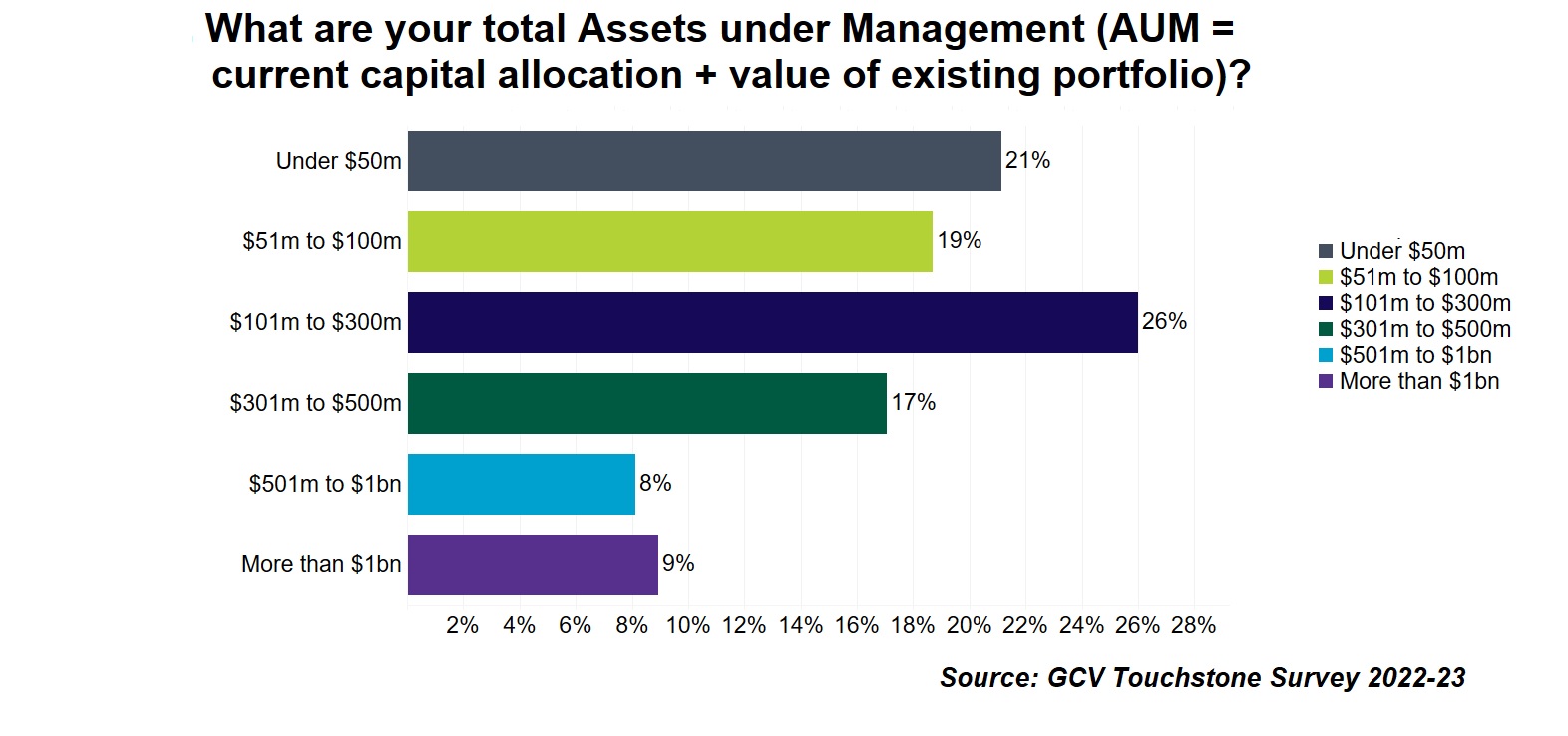

It is still very rare. Only 6% of the CVCs we surveyed in our annual GCV Touchstone survey had a fund size beyond a billion dollars, and just 9% had more than a billion dollars in assets under management.

But the number of large funds are on the rise. While the behemoth Softbank Vision Fund may have caught a lot of the headlines in recent years (both positive and negative), there are many units that have grown more quietly to this level, including the investment arms of oil and gas major Saudi Aramco, pharmaceutical firm Bayer and telecoms, IT and consumer electronics manufacturer Nokia.

We spoke to these teams about how CVC management changes after reaching a billion. They told us that while a big fund has many advantages, especially in ways it can support portfolio companies, there are downsides, too, such as increased scrutiny from the parent corporation.

Accident or by design?

None of the three units we looked at had necessarily planned to grow as big as they did, although they were created in a way that left this possibility open.

“We were set up to make significant investments and also to co-create new companies,” says André Guillaume, VP and head of Brand and Community Engagement at Leaps by Bayer.

The Leaps by Bayer venturing arm started out in 2015 with around €300m initially. It took it several years to reach the €1bn mark. The unit runs a portfolio of 55 companies, €1.7bn invested. It was recapitalised with €1.3bn by its corporate parent in 2022, which it intends to deploy over the next few years.

“We have clearly defined goals and those involve investment in a disruptive technology. It’s nice to be able to invest big but we don’t do it just for the sake of investing big,” says Guillaume.

Aramco Ventures, meanwhile, was launched in 2012 as a $500m evergreen programme named Saudi Aramco Energy Ventures (SAEV), with a mandate to invest in technologies that could bring value to its corporate parent. Investments have ranged from core oil and gas tech, to AI, additive manufacturing and sustainability technologies. In the past five years, the investment focus has shifted much more to the latter two, according to Bruce Niven, head of strategic venturing at Aramco Ventures.

In the past few years, Aramco launched two $1bn funds – Prosperity7 Ventures and the $1.5bn Sustainability Fund. Saudi Aramco supplied capital for both.

Launched in 2019, Prosperity7 is largely structured like a traditional venture capital (VC) fund, focused on deep tech from the US and China. The vehicle is driven by diversification and financial return objectives with a 6-year investment period.

The $1.5bn Sustainability Fund was set up with a two-fold objective in mind – to support the decarbonisation of Saudi Aramco’s own operations and help the company to develop new lower carbon fuels businesses, such as hydrogen, ammonia and synthetic fuels.

NGP Capital started life in 2005 as Nokia Growth Partners, with an initial fund of merely $30m, according to PitchBook. Soon after, in 2007, it raised its second one sized at $225m. The third one of $350m came in 2012, followed by the fourth also of $350m in 2016. Most recently, NGP Capital, which runs as an independent firm, raised its fifth one of $400m in 2022. All of these funds were raised with its corporate parent Nokia as a sole investor.

The fund was started with an intention of making big returns, says Paul Asel, founding partner of NGP Capital. “When we started, Nokia’s CFO told us: ‘We want you to be material and make an impact on the corporation.’”

Its second fund (NGP II), started in 2007, ended up being particularly successful, with the original $250m fund creating seven public companies and six unicorns from 28 investments. (Read Asel’s full version of how this was done here).

“NGP Capital has become material to Nokia over time. Investment analysts inquire about NGP’s performance. We welcome the attention as it increases the level of corporate engagement and our potential impact,” says Asel.

The benefits of being big

There are definite benefits to size, the most obvious one being the ability to support portfolio companies better — not just in financial terms but with a number of other services.

“We not only provide capital but also very active support. In some cases, we have helped startups with beta IP, i.e. patents they otherwise couldn’t get access to,” says Guillaume from Bayer.

“Oftentimes young companies, founded by scientists, lack business expertise, so we help them with HR, legal and branding support, among other things. We also connect them with other portfolio companies. We put up networking events for them.”

Asel agrees that, as NGP Capital has grown in size, it has been able to beef up its corporate business development function. “Increased size brings economies of scale that allows to engage more actively with our partners. Any investor should provide value in addition to capital. With a larger size and bigger team, NGP Capital has more experts investing in new technologies, which enables us to add more value to the companies in which we invest,” he says.

NGP Capital has also been able to make investments in its own processes, such as developing a proprietary AI-based analytics system, called Q, to monitor potential investments.

“It monitors over one million businesses across the globe,” says Asel. “This AI-based system gathers information from different sources and helps the team become more efficient in sourcing and evaluating potential investments. We have also automated our internal processes as we manage all pipeline activity through Q,” says Asel.

Another operational benefit is having a big global team, says Aramco’s Niven. “We started out as 25 or so people but now we are 65 people across Saudi Arabia, the US, Europe and China,” he says.

Drawbacks of being big?

One of the biggest drawbacks of having a big fund is an increase in scrutiny from the parent corporation. There is a natural tension, according to Asel from NGP Capital, between a CVC unit, which has long time horizons and stochastic returns, and corporations, which prefer predictable, smoothed returns. This can fly under the radar when the CVC unit is little more than a rounding error for the corporation but comes into the spotlight when the fund is larger.

“The financial impact of variable returns increases with more assets under management. Strategic value should also increase with corporate fund commitments given the opportunity cost of capital and need to demonstrate strategic benefits during financially lean periods,” he says. “Increased fund commitments raise the bar for us to deliver value, which is fundamentally good as it aligns incentives to deliver both strategic and financial returns. As Nokia reminds us, we aim to be financial first but not financial only.”

Niven of Aramco Ventures also admits that with scale, the venture group has become more visible. “There is more awareness about us and what we do and much more visibility at senior levels in general. With current AUM of $3bn, the risk is also more significant, so we have strengthened our compliance and risk management but with a focus on remaining efficient.”

The added structural complexity, however, has not necessarily hampered the speed of dealmaking for Aramco Ventures. “The deal approval process can be, at times, a challenge in term of getting everyone scheduled; but, overall, with time we have learned how to become more efficient with it. We have introduced a fast-track approval process for small ticket investments,” says Niven.

In fact, a larger fund size can help in terms of deal speed, he says, as Aramco Ventures now has more flexibility, for example, to make more bets in very early (seed) stage enterprises.

Limits to growth?

Despite the outsized example of Softbank’s $154bn Vision Funds, most of the investors we spoke to felt there were limits to the size a corporate venture fund can grow to.

Some of those have to do with pure internal capacity. “There definitely is [a limit],” says Guillaume of Leaps by Bayer. “We’re already quite big with 55 portfolio companies and we try to take board and observer seats. We have a team of 20 people, 11 of whom are taking board or observer seats, so they are feeling it. I don’t think we will go much beyond 75-80 companies maximum. The team is not that big, after all, and we are hiring.”

Asel of NGP Capital thinks this should ultimately be a function of corporate strategy and objectives: “Peter Drucker says that innovative companies have two responsibilities: maintaining the present business and searching for opportunities for new business tomorrow. The latter is an exploratory function and the domain of R&D, M&A and CVC. So, it is an allocative decision for each organisation. Companies with higher cash flows can allocate more capital to the exploratory function and to CVC activities.”

In some cases, the constraints may be down to the specific industry a corporate venture unit invests in. “I’d say our Prosperity7 could probably grow significantly bigger because it has a broad mandate,” says Niven of Aramco Ventures. “However, for strategic ones, there is a limit as to how many investments you would want to make within your strategic addressable areas. We could maybe double our strategic fund size but that would begin to stretch the boundaries of strategic relevance at that scale.”

In short, it is probably better to be big than not, although big funds need to be prepared to invest a lot more in governance and stakeholder management. It will be interesting to see what further best practices start to emerge as an increasing number of CVC teams join the billion dollar club.