Corporates continued to invest in real estate tech through 2022, unlike their traditional VC peers. We look at how this might play out.

Despite bleak short-run macroeconomic prospects, corporates have continued to invest enthusiastically in real estate tech and services through 2022, unlike their traditional VC peers. This investor optimism is targeting earlier- and seed-stage investments and seems to be ultimately driven by a serious housing shortage in the US, which is bullish for the sector in the long run. We take a deep dive into how this might play out.

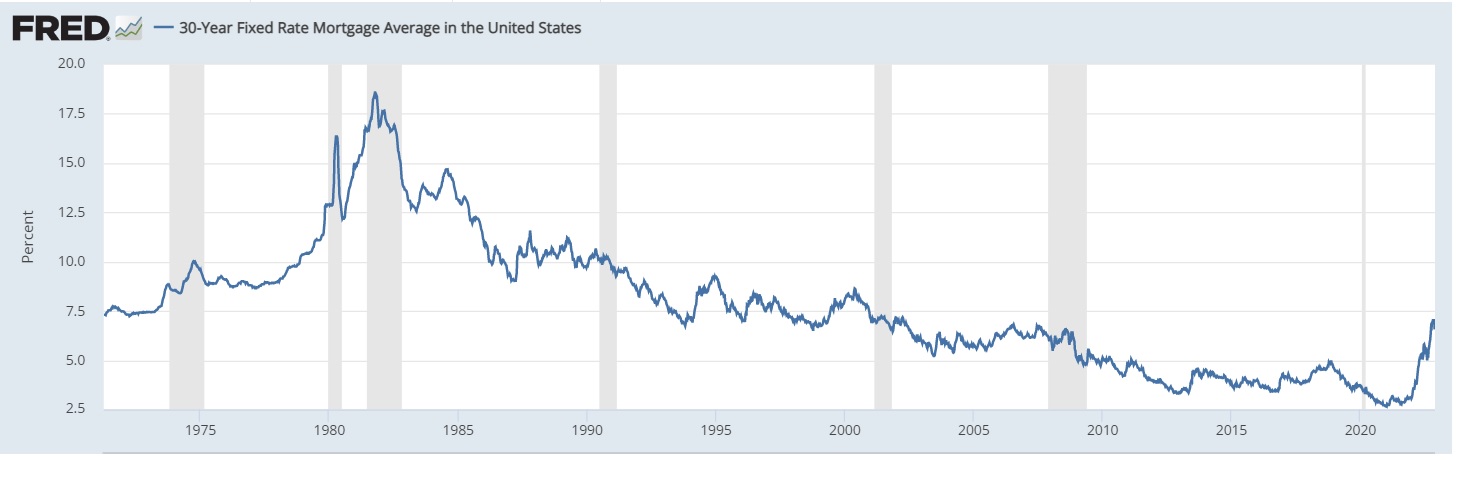

With ongoing interest rate hikes and an increase in mortgage rates, the macro picture looks, on the face of it, gloomy for the real estate sector, at least in the short run.

According to the Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) base, average 30-year fixed mortgage rates recently rose above 5% for the first time since around 2011, as shown on the chart here. This doesn´t seem to have stopped corporates from investing in the space.

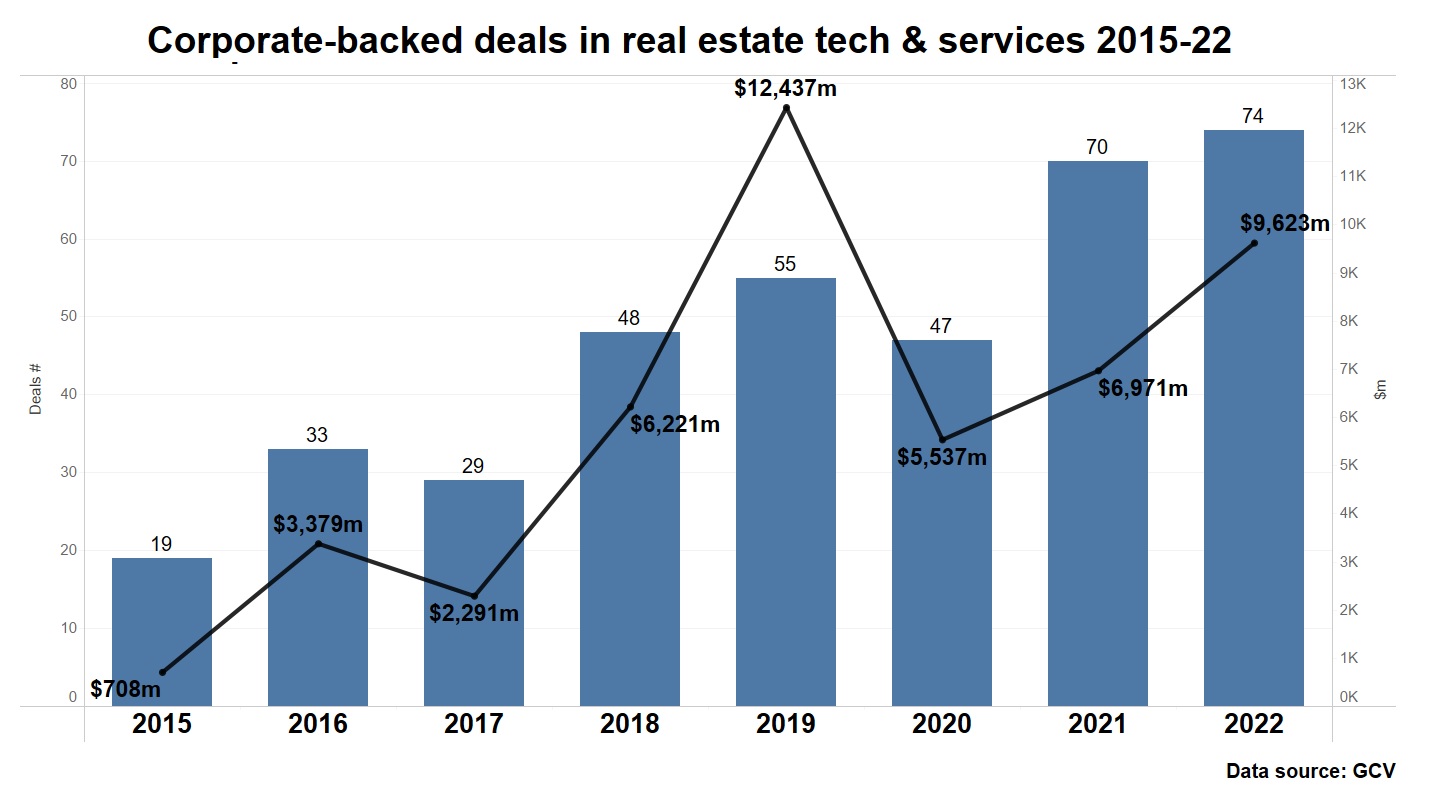

In fact, last year we saw corporate-backed deals in real estate tech and services increase in number slightly compared to the previous year (74 rounds reported in 2022 versus 70 in 2021).

The total estimated dollar amount in those deals increased by 38% from $6.97bn in 2021 to $9.62bn in 2022. If anything, amid a less than accommodative monetary environment, this suggests that a certain group of investors are being rather bullish on this space.

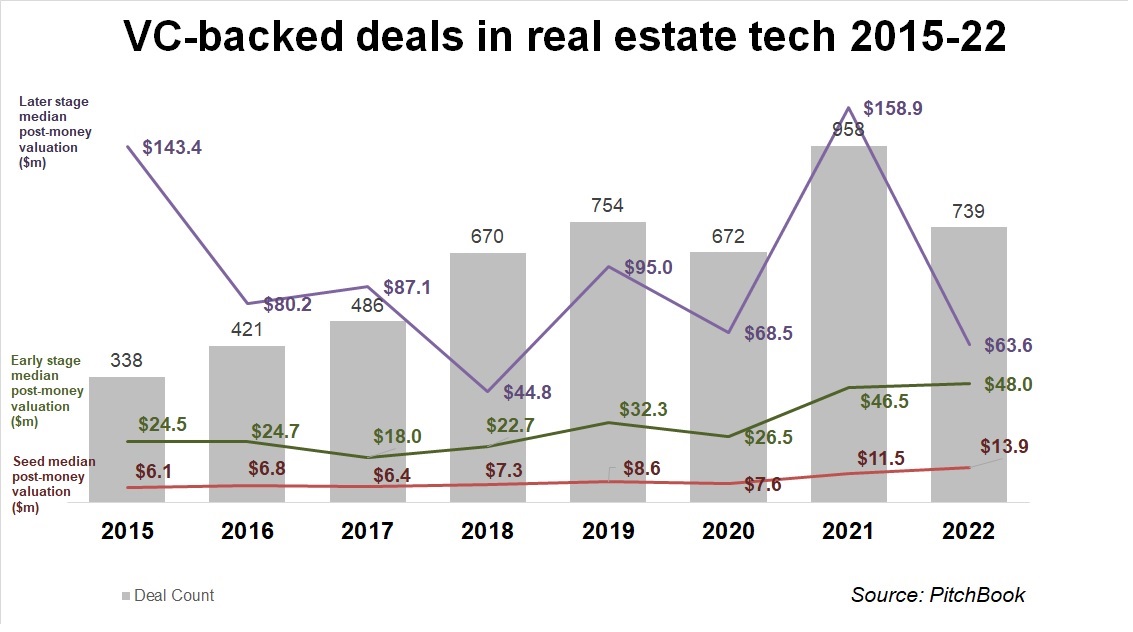

Even more interestingly, corporate investors appear to be diverging from the rest of VCs here. The global number of total VC deals in real estate tech dropped by 17% to 739 from 958 in 2021, according to PitchBook.

There was also a sharp divergence between early and late stage deals. As the chart below shows, later stage median post-money valuations plummeted from $158.9m to $63.6m but that was not the case of early-stage and seed rounds. Median post-money valuations for seed rounds expanded – from $11.5m in 2021 to $13.9m, implying a 21% increase. In the case of early-stage deals, the median valuation went up from $46.5m to $48m over the same period.

These patterns are similar to overall corporate investment trends we observed in our yearly analysis of the overall 2022 CVC data — but the in the real estate sector the trend has been particularly sharp.

“We have definitely seen a drop in overall deal volume and it is most prominent in later stage deals,” says Raj Singh, managing partner at JLL Spark, the venturing arm of commercial real estate firm Jones Lang LaSalle. “I’m not sure that we have seen an increase in early-stage deals but those have been more robust and we have seen them decrease only slightly or remain flat,” he said.

Singh believes valuations for early-stage companies have stayed stable for several reasons. Their cash burn rate is usually much lower than that of a later-stage one, and as they are pre-revenue, they are not judged on factors like sales multiples.

Such companies often do not expect a significant turning point in their accounts foreseeable future. “Valuations also have to do with how long it would take such companies (at early stage) to generate revenues or become profitable versus how long a downturn might last,” he said. “The majority of early-stage companies don’t expect such things within the next two years.”

Sustainability imperative

Each corporate real estate investor has a slightly different focus, but there are some common themes in recent deals. New IoT and AI tools that help owners to make their buildings smarter are popular investment targets, in part because these can help with sustainability goals.

“Studies show that 40% of global carbon emissions come from buildings. Despite the [current] economic conditions, the sustainability imperative does not change, as there is increasing pressure from governments to punish building owners who fail to keep their carbon footprint in check,” explained Singh. “Valuations in this space have stayed quite robust.”

Overall, despite the inherent cyclicality of the real estate market, JLL Sparks take a very long term view, according to Singh.

“Fortunately, we have a very forward-looking board of directors and we expect to continue to invest in the coming years. In fact, we made roughly the same number of investments in 2022 as in 2021,” he says.

“We understand most portfolio companies won’t be immediately accretive to the bottom line. It would take some time even to the most prepared ones.”

Bullish case for US real estate?

There is also a structural reason to be bullish about the US real estate market. The “millennial” generation has reached the age of becoming homebuyers. Many studies from recent years show that the majority of millennials consider homeownership a top priority and that the majority of them are or would be first-time homebuyers, as cited in this piece by Raleigh Realty. There´s no shortage of talk in the media about millennials struggling with affordability either.

But even if we take the conventional wisdom view that the best cure for high prices is high prices, there is a missing piece. Unaffordability of homes is a symptom of a nearly nationwide shortage in housing.

In a recent piece for The Atlantic magazine, Annie Lowrey explored the question of how many homes should be built to make coastal cities affordable again for middle-class and working-poor families. She found no easy answer to this but highlighted the issue.

Measuring the shortage

Just how bad is the shortage? It is a notoriously hard problem to measure, not least because there is no universally agreed-upon methodology.

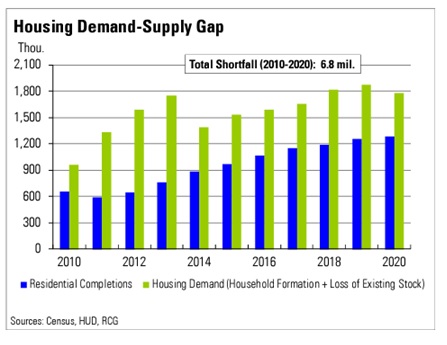

In the simplest terms, for a housing market to function well, the number of houses being constructed must comfortably exceed the demand created by population growth and other demographic changes. New housing construction is often juxtaposed with household formation, among other factors.

The White House, citing Moody´s Analytics estimates, reported in 2022 a shortfall of “more than 1.5 million homes nationwide.” Notably, these numbers used by policymakers appear even modest, compared with others.

A 2021 study of the Rosen Consulting Group, for example, calculated that “household formation alone exceeded housing production by nearly 3.2 million housing units from 2010 to 2020.” The study went even further methodologically to estimate a shortage of around 6.8 million units.

A similar study of the Up For Growth organisation entitled “2022 Housing Underproduction™ in the U.S” assessed a nationwide underproduction of 3.79 million units in 2019 versus 1.65 million in 2012.

Similarly, a 2021 study by Freddie Mac computed a supply deficit of 3.8 million housing units that were needed to meet demand and “maintain a target vacancy rate of 13%”.

Some estimates are even more stark. In a discussion paper for the IZA Institute of Labor Economics on the understated housing shortage in the US, authors Corinth and Dante estimated a shortage of 20.1 million units by 2021 or the equivalent of 14.1% of existing stock of homes. The paper maintains the shortage was so severe due to excessive local building regulations.

The numbers may vary but the overall message is clear: supply has not kept up with demand. That, ultimately, will continue to drive the need for housing, whether in homebuilding or in real estate services, for possibly the next decade. And it will keep corporates investing in the real estate space bullish.