Many of the first wave of alternative materials — from pineapple leathers to silk alternatives — failed. A handful of new startups, however, are attracting money and partnerships. Can it work better this time?

Innovators in the novel material space might find themselves struggling to convince investors to take another bet. In recent years, many next-generation fibres have flopped; several start-ups once hailed as vegan game-changers, from pineapple leathers to silk alternatives, have failed to scale. Despite a few splashy pilot programs, most fashion brands cling to synthetic and animal-derived materials. It can’t hurt, then, for a founder to arrive at a pitch meeting with a parlour trick.

That’s one tangible way Stephanie Downs, CEO and co-founder of US-based biomaterials company Uncaged Innovations, has demonstrated the readiness for leather alternatives that aren’t made entirely of plastic. “When I was doing the investor raise, I’d give people a piece of real leather and a piece of ours,” she explains. Then she’d ask: which is which? “At least 50% of the time they’d think ours is the real leather; 100% of the time, they’re struggling to tell the difference.”

Uncaged is unlike other leather alternatives that rely on mushrooms (that is, mycelium) or fruit pulps (like pineapple leaves or apple skin waste) often held together by some percentage of plastics. The company fuses proteins from agricultural grains to replicate cowhide’s structure, a process developed by co-founder Dr Xiaokun Wang, whose biomedical research at Johns Hopkins included inventing corneal implants from biomaterials. Uncaged sells its material with and without a bio-based polyurethane top coat, not derived from fossil fuels though still a polymer structure; never amounting to more than 1% of the final product.

There is a gap in the market for more sustainable alternatives that can match leather’s performance, according to Dr Kate Hobson-Lloyd, sustainability manager at rating platform Good On You (where I serve as editor-at-large): “It’s clear that there is a need and a want for a material that is not leather but behaves like it,” she says. But having tracked novel materials for more than a decade, including as a former editor at trade publisher Textiles Intelligence, she notes that costly barriers have kept many start-ups stuck in expensive limited runs. “The ones that we’ve seen so far, they’re mostly piloted in luxury products. That’s not accessible to your average consumer.”

While the expertise in collagen, the protein structure that gives leather its characteristic strength and durability, may set Uncaged apart, what makes it competitive is its price point, which Downs says is comparable with quality leather.

That’s led to a series of wins. In late 2024, Uncaged raised $5.6m in an oversubscribed seed round and collaborated with several fashion brands. Last year, it announced partnerships with carmakers Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) and Hyundai to develop automotive interiors. In December, Academy Award-winning actor and longtime vegan activist Natalie Portman (pictured above) joined as strategic partner and equity investor, the kind of celebrity visibility most startups have so far lacked, which might help raise awareness among consumers.

“I remember the days when Stephanie came over to the UK and we had almost a post-it note size sample. We’re now talking hundreds of metres of a roll.”

Mike Smeed, managing director of InMotion Ventures

“It’s been an amazing three years,” says Mike Smeed, managing director of InMotion Ventures, JLR’s corporate venture arm, which led the investment across Uncaged’s last two funding rounds. “I remember the days when Stephanie came over to the UK and we had almost a post-it note size sample. We’re now talking hundreds of metres of a roll.”

In a sector littered with past failures, a handful of companies are attracting capital and customers, not by leading with sustainability claims but by solving business problems their predecessors couldn’t quite crack. They’re expanding to markets beyond fickle fashion.

A contested market

A range of innovations are competing for traction. Faircraft, a French start-up, is developing cultivated hides after acquiring much of the patent portfolio of collapsed competitor VitroLabs in a US asset sale last year. This remains untested at a commercial scale.

Ecovative’s mycelium platform has secured partnerships with brands including Reformation and PVH Corp (owner of Calvin Klein) and raised more than $100m. London-based Modern Synthesis, which grows bacterial cellulose onto textile frameworks, has become the first material supplier to receive Positive Luxury’s Butterfly Mark, a certification of high standards of environmental, social, and governance standards for luxury brands. Cambridge-based PACT, making collagen-based leather alternatives, closed a series A of more than £16m in 2025, in a round led by Forbion and HV Capital.

But the list of closures and pivots is remarkably bleak. As the Financial Times’ Annachiara Biondi documented in a November investigation into “the sustainable fabrics market collapse,” several of the most heavily funded ventures in the sector have folded. MycoWorks shut its South Carolina plant despite raising more than $200m; Bolt Threads discontinued its textile alternatives; Natural Fiber Welding wound down; Renewcell’s textile-to-textile recycling venture went bankrupt; and pineapple leather Piñatex maker Ananas Anam entered administration.

These failures have left a trust deficit, and surviving companies have to tackle it head-on. “Sustainability for sustainability’s sake isn’t enough,” Smeed says. “It has to perform. And it has to be on cost parity or even better against a product that has been cost-engineered all the way through its value chain for fifty, sixty or even more years.”

Smeed says his team evaluated roughly 40 innovations before selecting Uncaged for investment. Downs believes the issue isn’t the lack of appetite in the market, but start-ups that failed to meet its demands. “Investors might be thinking, well, the market must just not want these solutions,” she says. “But it’s really more that the innovations weren’t meeting the mark.” The question is, can the few companies showing signs of success fulfill their great promise? It’s a question that’s been asked before.

Is leather the new fur?

In November 2023, as world leaders gathered for Cop28, English designer Stella McCartney unveiled her first collaboration with BioFluff, a Paris and New York-based start-up making faux fur without plastics. Its demand has accelerated with the wave of fur bans. New York Fashion Week will ban fur starting in September; and in December, even the designer Rick Owens, infamous for his use of fur, finally caved to pressure from activists at the Coalition to Abolish the Fur Trade, which had protested outside his boutiques.

“Fur bans have been definitely very helpful to engage more fashion brands and get investor interest,” says co-founder and chief commercial officer Roni GamZon. BioFluff has moved well beyond pilots. It is launching products into commercial collections “every week,” she says, and recently debuted material with JNBY, one of Asia’s largest luxury fashion groups, in their menswear core line.

But GamZon is looking beyond fashion for growth. Recently, her company has diversified into plush toys, where volumes are higher and orders steadier. “Lots of material innovation relies heavily on fashion, which is a very difficult market.”

“Fur bans have been definitely very helpful to engage more fashion brands and get investor interest.”

Roni GamZon, co-founder and chief commercial officer, BioFluff

Downs believes conventional leather is headed in the same direction. “I definitely think leather is the new fur,” she predicts. The existing market for synthetic leather, already a substantial share of the overall leather market, suggests consumers are broadly open to alternatives, though Downs is clear that fossil fuel-based synthetics are not the answer.

But as with BioFluff, the Uncaged business success might not rely solely on fashion. Downs previously held a key role at PETA, where she negotiated with Tesla, which began removing leather from its vehicles in 2017. Volvo has committed to phasing it out by 2030. Renault has followed.

That attention from automakers and their investors has been essential. Downs credits InMotion’s investment with helping attract additional venture capital at a time when the alternative fibre market’s reputation was bruised. “CVCs really cannot underestimate the power of them putting a cheque in and how that helps bring in other VCs,” she says.

The four boxes to tick

Any start-up CEO on the phone with an investor will sound confident, and Downs is no exception; I spoke to her and Smeed on the same video call. But when she describes what she calls the “four boxes” that brands require of any new material, the framework lands because it implies what prior ventures could not deliver: quality, scale, price and sustainability.

“Brands are not going to buy something because it’s a good idea,” she says. “I think a lot of people went into the space so focused on sustainability that they lost sight of the other three.”

That’s not to say the sustainability claims don’t matter. Smeed explains that Uncaged got its backing not on its sustainability pitch alone, but because it met the full set of needs. “Consumers want choice in terms of the types of material, the colours, the texture, the feel,” he says. “But what they don’t want to make a choice on is the environmental credentials.” Sustainability, in this framing, needs to be baked in.

The companies still attracting investment have a manufacturing lesson, too. GamZon built BioFluff to run on existing factory equipment rather than investing in proprietary production. “We have zero capex and already have full-scale production capacity of over 65,000 metres a week,” she says. “I think we will see more companies unfortunately shutting down, especially ones that rely on creating their own factories.” Uncaged has similarly leveraged existing facilities.

What’s not yet proven

If sustainability is the fourth box, how robust is the case? Uncaged’s own data is promising.

Downs shares facts based on a third-party screening life-cycle assessment (LCA) that suggests her novel material produces 95% less greenhouse gas emissions, uses 89% less water and 71% less energy than animal leather. But these are preliminary cradle-to-gate estimates, not independently verified, and Downs is transparent about the difficulties: the available life-cycle data for leather varies enormously depending on where you draw the system boundary. These comparisons are, at best, ballparks. “It’s just so hard,” she says. “You look at [leather’s] numbers and they’re all over the place.” But she says virgin leather’s negative impacts are significant, whatever number you’re referencing.

Materials represent one of fashion’s most significant environmental levers, which is why this space attracts investment and scrutiny in roughly equal measure.

But Hobson-Lloyd makes clear that material innovation alone does not resolve the sector’s fundamental problems of overproduction and overconsumption. “Materials can’t be the be all and end all,” she says. For a thought experiment, imagine a brand deploying a novel material within a linear take-make-waste system; it may achieve less than one using conventional materials in a genuinely circular model.

As EU legislation tightens, brands will increasingly need that data to back their claims. But even LCAs are imperfect, and a narrow focus on environmental outcomes might miss other key ESG impacts. “The labour side of this stuff needs to be considered,” she says. “It’s all shrouded in the sexy tech speak, and that element gets brushed under the carpet.”

Such scrutiny often comes with growth. Uncaged is planning manufacturing expansion into Asia and Europe this year, with further automotive and fashion brand announcements expected. The challenge, as Downs frames it, is staying focused while demand pulls in every direction: “People contact us wanting to use it in basketballs, in yachts, in yoga mats.” The list goes on, and that’s promising.

“I’m thankful to the first movers in the space. They built a market. But I consider us a second mover.”

Stephanie Downs, CEO and co-founder of Uncaged Innovations

This promise isn’t unlike the companies that came before, which touted big claims, attracted investment, and ultimately failed to deliver. Perhaps the companies still standing have grasped what killed their predecessors. The material has to earn its place on performance, price and scale and not on the environmental potential alone. It has to tick all the boxes.

Downs, who started her first company in 1998, has seen enough market cycles to know that first movers rarely win. “In most industries, the first movers aren’t the ones that are the breakout technologies,” she argues. “Before we had Facebook, we had MySpace and Friendster. Before we had Google, we had Ask Jeeves and Netscape.” Ergo, before there was grain leather, there was pineapple leather?

“I’m thankful to the first movers in the space. They built a market. But I consider us a second mover.” The question now is whether the second movers can prove the business.

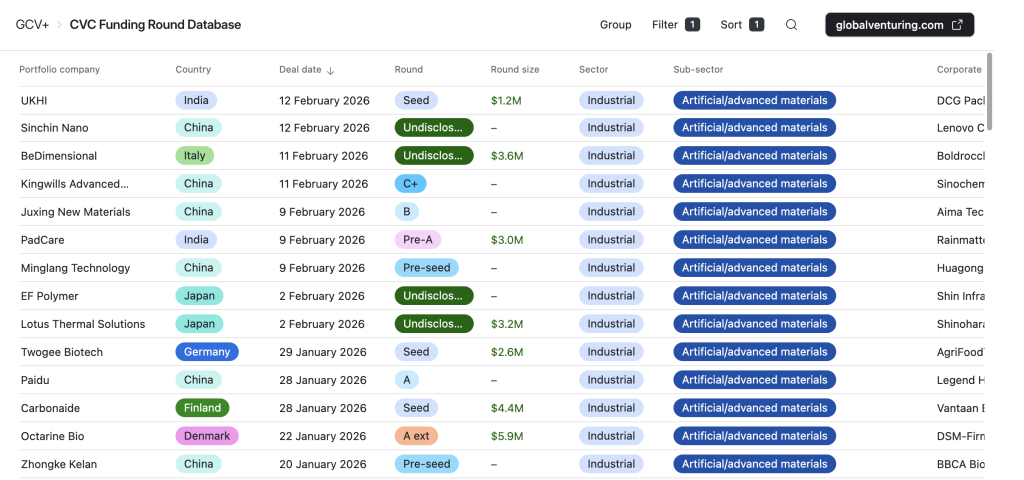

See all the recent corporate investments in advanced materials startups in The CVC Funding Database