New energy storage technologies are charging ahead as the supply of commonly used materials face a supply crunch.

When Dutch electricity storage startup Elestor announced a €30m ($29.2m) financing round for its hydrogen bromine flow battery in August, CEO Guido Dalessi’s phone started ringing off the hook. In one day, the entrepreneur had 30 voicemails from callers enquiring about the technology. “For battery manufacturers, the world has gone crazy,” says Dalessi. “There is so much demand, it is unbelievable. And it will stay like that for a while.”

Many reasons are behind the strong interest in electricity storage. Batteries that store energy for when it is needed will be critical to the transition to cleaner energy. It will be essential for stabilising the increasing amounts of wind and solar generation on the grid.

And battery storage is a crucial part of the manufacture of electric vehicles. As consumers switch preferences for electricity-powered cars, the demand for batteries that allow owners to drive long distances will keep on increasing. The International Energy Agency says the world will need two billion battery electric, plug-in hybrid and fuel-cell electric light-duty vehicles by 2050 to hit its net zero carbon emissions goal.

But supply constraints of a critical material are looming over the sector. Most battery storage technology relies on lithium, a silvery-white metal used to make batteries in EVs and mobile devices. The demand for lithium is expected to be so high from electric carmakers that the world could face shortages by 2025, the International Energy Agency says.

Increased demand for lithium is already evident in the almost sixfold price increase for the material since 2020. Reserves of lithium are also found in just a handful of countries, including Australia, China, Chile, Argentina and Bolivia, which exacerbates supply constraints. And extracting lithium requires high volumes of water, putting a strain on countries that are prone to drought.

These constraints have driven the emergence of alternative battery storage technologies that have gained the support of investors.

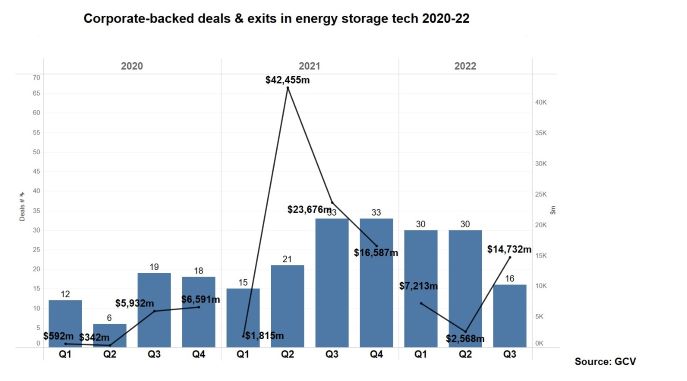

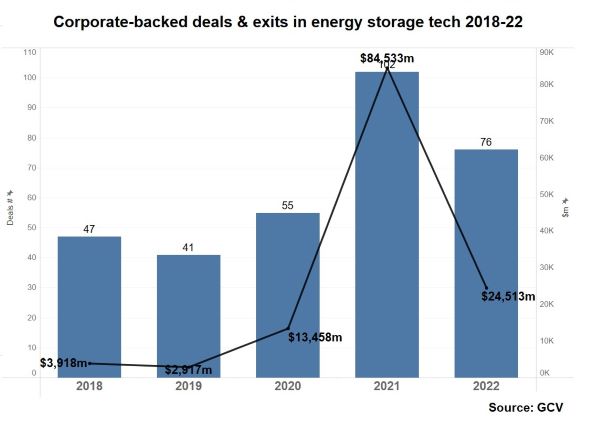

Energy-related investments have held up more than other sectors this year in the face of a declining economy. GCV data show corporate-backed energy storage tech deals totalling $25.5bn so far in 2022. This is a drop from the $84.5bn in 2021, but investments rebounded this quarter. Corporate-backed financings of startups tracked by GCV totalled $14.7bn in Q3 of 2022, an almost fivefold increase over Q2.

Recent deals include a $450m series E financing for Form Energy, a US developer of long-duration iron-air battery technology designed for the electricity grid. Metals and mining company ArcelorMittal is the corporate investor in the deal announced in October.

Moxion Power, a California-based maker of mobile energy storage, raised $100m in series B funding in September. Corporate investors included Amazon Climate Pledge Fund, Microsoft Climate Innovation Fund and Marubeni Ventures, the corporate venturing arm of the Japanese trading and business conglomerate.

Smaller scale financings include power grid equipment provider G&W Electric’s commitment of $3.6m for Intelligent Generation, a US energy storage optimisation tool maker, in May.

A lot of recent battery tech deals have been designed for balancing renewables on the electricity grid. This reflects the wider scope for developing alternatives to lithium-ion in this sector as opposed to the electric vehicle manufacturing industry, where lithium, for the moment, dominates battery technology.

Hydrogen-bromine

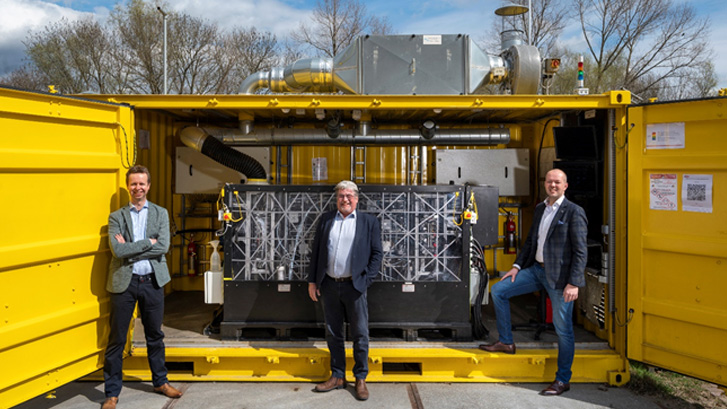

In the Netherlands, the team at Elestor are planning to build a pilot project next year to develop the company’s flow battery technology after receiving the large cash injection in August. Equinor Ventures, the corporate venture arm of Norwegian oil company Equinor, is lead investor. The venture capital unit of Dutch tank storage company Royal Volpak also committed capital to the financing round.

The flow battery uses hydrogen and bromine, which are plentiful and cheap, and can store energy between six hours and one week, says CEO Dalessi. The battery technology is designed to store energy generated from wind and solar parks and can last between 15 and 20 years. The technology requires large tanks to store the hydrogen and bromine, which is the reason the company partnered with tank storage company Volpak, which has facilities located at seaports.

Among the challenges the startup faces on the path to commercialisation are difficulties sourcing some parts due to limitations in integrated circuit chips. Certain materials have also increased in price due to higher oil prices. Dalessi says it is difficult to hire people with the right skills to meet its growth targets “but so far we have managed quite well,” he says.

The company needs to scale up quickly to bring its production costs down and make the technology competitive with lithium. “Everyone is comparing our prices with lithium prices. Lithium batteries are built at giga factories at maximum economies of scale. We can only reach that price level if we start producing at certain quantities. My go-to-market strategy is to team up with the large developers of wind and solar farms. They will give me the demand for large volume production. The scale will reduce the price very fast,” says Dalessi.

Compressed air

Another potential grid storage approach uses compressed air technology. This is particularly suitable for offshore wind where pumped hydro storage could be embedded in the base of wind turbines. When the wind blows, water is pumped into a tank and air is compressed against it. This compressed air is what stores energy. When the water is released, the air pushes out through a pump that generates electricity when it is needed.

Thermal

Thermal storage solutions are also in the works. One approach is to use molten salt. The salt is heated with renewable energy. The energy produced from the heated salt is then used to heat water, which is run through a steam turbine to generate electricity.

Sodium-ion

Sodium-ion battery technology has made the most headway. Faradion, a UK startup, develops sodium-ion cell technology that can be used for back-up power as well as for low-cost electric transport such as e-scooters and e-bikes. Faradion, which counts electronics manufacturer Sharp as a corporate investor, was acquired by Indian conglomerate Reliance Industries in 2021.

Sodium-ion batteries for electric vehicles do not have the energy density – how far you can drive on a single charge – that lithium-ion batteries have, but it is the nearest term battery technology that completely decouples from lithium, says Thomas Bartlett, deputy director of UKRI Faraday Battery Challenge at Innovate UK, the UK government’s battery research programme. “The supply chain [for sodium-ion] needs to be developed, but it is making headway in stationary storage applications,” says Bartlett. Large companies that are backing sodium-ion battery technology include Chinese energy tech company Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., which is developing a sodium-ion supply chain.

Investors reluctant to finance large startup costs

A lot of innovation has been happening in battery design for electric vehicles to make them more efficient. Solid-state batteries are one innovation that increases energy density while using less lithium. The technology replaces liquid electrolyte used in regular batteries with solid material. This allows for pure lithium anodes to be included in the battery which improves performance.

UK electric vehicle battery startup Britishvolt, which counts mining company Glencore as an investor, is part of a consortium set up to develop and commercialise solid-state batteries in the UK. Johnson Matthey, a UK sustainable technologies maker, and Emerson and Renwick, a UK maker of engineering equipment, are also part of the group.

It is challenging for startups to raise large financings in the UK, says Bartlett. “The £10m [$11.3m] to £15m mark is where we need more investment,” he says. “For most battery companies, the capital requirements to scale are large and early for material and cells. A lot of companies are trying to raise large amounts of capital to scale. We are seeing more companies having to go to the US to raise funds because there is more acceptance of that capital.”

The UK government funded the UK Battery Industrialisation Centre to help startups to scale up production. The centre fills the gap in financing that startups face when trying to commercialise their technologies. Britishvolt has used the facility to develop production of its batteries.

As various battery technology companies seek financing, investors will have a broad spectrum to choose from. No one technology will likely supersede others as the rush to electrification shows no sign of abating.

Says Bartlett: “In talking to investors, I get the impression that they are waiting for the sure bet when it comes to batteries. What is becoming clearer and clearer is that because of supply chain constraints and diverse applications that lithium-ion batteries can be applied to, there will not be one technology that will dominate.”