Funding numbers are down as Southeast Asia's startups have failed to keep track with the move to deep tech, but they can overcome that by adopting an international outlook.

Southeast Asia’s startups are going through a lean period as early-stage capital moves away from consumer-focused companies to deep tech, and the region’s startups and corporates need to adjust their thinking, a range of local investors tell GCV.

“For the past two years, it’s been quite tough for the ecosystem as a whole,” says Edgar Hardless, CEO of corporate VC unit Singtel Innov8.

“We’re still going through a period where I think investors are more cautious. Companies have had to tighten their belts and accelerate their plans to get to break even more quickly, so they can extend their runways. Most people in the ecosystem were hoping that things would improve in the second half of this year, but I think that’s uncertain now.”

It’s a far cry from the second half of the 2010s, when the region’s startups were supercharged by a range of app developers in consumer-facing areas like transport (Grab and Gojek), ecommerce (Tokopedia and Sea) and travel (Traveloka) that shot to multibillion-dollar valuations, often before going public.

Southeast Asia was primed to be successful for those startups because of a relatively large population of consumers with high adoption of mobile devices. In theory, that base layer of consumer companies would create a market for service providers in areas like logistics and fintech, and then for more general business-to-business (B2B) companies. The problem is that local startups have progressed to that second stage but not the third.

Vishal Harnal, who oversees venture firm 500 Global’s Southeast Asian activities as managing partner, says that globally, apart from market leaders in areas like ride hailing or accommodation platforms, most successful startups over the past 15 years have been in software, particularly enterprise software. Southeast Asia, however, has not produced enough of these enterprise software businesses.

“There’s very little B2B software [in Southeast Asia], almost none of it. And if I look at our US portfolio, all of our big winners are in that category”

Vishal Harnal, 500 Global

“One of the things we’ve realised is that there’s very little B2B software [in Southeast Asia], almost none of it. And if I look at our US portfolio, all of our big winners are in that category,” he says.

“People still try and chip away at the bottom layers but it’s hard to build a new ride hailing company or a new property portal listing companies once the incumbents are set up.”

Harnal believes a significant reason for that shortfall is that there aren’t enough large corporates in the region to take on the large subscription contracts that make enterprise software companies successful, and international players have a whole world of products to choose from. The issue has been exacerbated over the past two years, as more and more of the funding pie goes to startups specialising in deep tech, especially artificial intelligence.

Another problem is that building a deep tech ecosystem needs an ecosystem of academics, big tech corporates and deep-pocketed investors to attract promising young entrepreneurs, as in places like Silicon Valley. In Southeast Asia, Singapore in particular has made efforts to help through visa quotas and government funding, but it hasn’t been enough to grow that ecosystem.

Some investors, like Thailand-based Siam Commercial Bank’s SCB 10X unit, have responded by refocusing more of their efforts on areas like the US, pitching themselves as an ideal local partner for foreign deep tech startups looking to enter Southeast Asia.

“It’s a conscious decision because we know that all the good AI startups are coming from the US,” says the unit’s newly installed CEO, Kaweewut Temphuwapat. “We have all the networks here in Southeast Asia – 10 countries speaking 10 languages – so we can give them a good intro throughout those areas.”

Corporate VC needs to expand into new fields

Corporate VCs have traditionally played an important role in the region, but a notable issue is a lack of variety when it comes to strategic investors: the overwhelming majority of them represent either telecommunications or banking.

That can be an advantage for consumer apps, which can benefit from integration with a mobile operator partner, or for fintech products that can benefit from working with an established bank.

But there is a shortfall of local CVC investors in areas like software. The largest corporate VCs worldwide are investing on behalf of software tech giants such as Google, Microsoft, Salesforce and Nvidia – and Southeast Asia doesn’t have a local equivalent of that size.

“Maybe we need more corporate VCs to invest on the deep tech side”

Tai Panich, Aiconic Ventures

“Corporates tend to invest in the areas that are more aligned with their strategy,” says Tai Panich, CEO of AI and deep tech-focused venture firm Aiconic Ventures, who previously ran SCB 10X. “And maybe we need more corporate VCs to invest on the deep tech side.”

While Harnal sees CVC as a hugely valuable part of funding worldwide, he believes it isn’t taken seriously enough in the region or professionalised to the degree it should be at a corporate level, particularly in comparison to Japan or Korea. The attitude from too many large companies is still ‘we can do it ourselves’ or that ‘it’s not important’.

“Much of it is because many of these corporates that are domestically successful, or maybe even regionally successful, have enjoyed positions of incumbency for the longest time,” he adds.

“The lack of worry and the dominance within the domestic market creates what I would say is a lackadaisical approach towards venture capital. There are a lot of exceptions to this rule but generally, if I were to benchmark it against the United States and other developed markets, it doesn’t appear to be as sophisticatedly built out, and I think it needs to be so.”

That lack of hunger to innovate is being compounded by a lack of exits in the market. Southeast Asia has never been a big M&A market for tech startups because of the lack of local buyers. The IPO drought has hit as hard locally as anywhere else, and the mass-market app developers that racked up large valuations pre-IPO have found it hard to maintain them once they went public.

That has hit investor confidence, and in turn fundraising. The effect is especially noticeable in Indonesia where formerly active CVC units like Bank BRI’s BRI Ventures and Sinar Mas-backed SMDV have largely fallen silent in the past year.

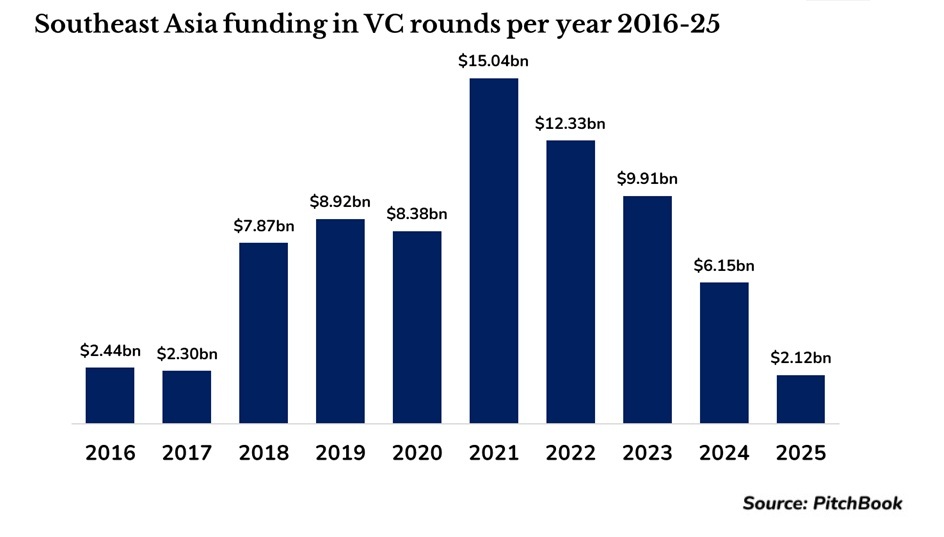

“People wanted to see a lot more of an IPO or exit window for the startup scene in Southeast Asia,” Panich says. “Funding has been a bit challenging. Compared to the year before, in 2024 funding actually dropped by something like 50%.”

The Singapore model: Launch local, think global

Southeast Asia could potentially catch up if it could move from a local to a more global focus, say investors.

The region’s startups may not be able to compete with artificial intelligence heavyweights OpenAI or Anthropic on the innovation end, but the advances and shortcuts in coding made by generative AI mean founders can build new products more quickly and cheaply than ever before.

“It’s never been easier to build software and it’s never been able been easier to market that globally”

Vishal Harnal, 500 Global

“The AI opportunity is when you think about AI as being a horizontal technology that applies across everything,” says Harnal. “When you think about the application layer, it’s never been easier to build software and it’s never been able been easier to market that globally and find a global audience of people willing to use software.

“And I think that’s what creates the opportunity, not just in Southeast Asia but anywhere in the world. You can be sitting in Timbuktu and build a global company if you wanted to, you just need to figure out a way of getting what’s in your mind’s eye into reality and making sure that whatever it is you build is solving a base customer problem that is global.”

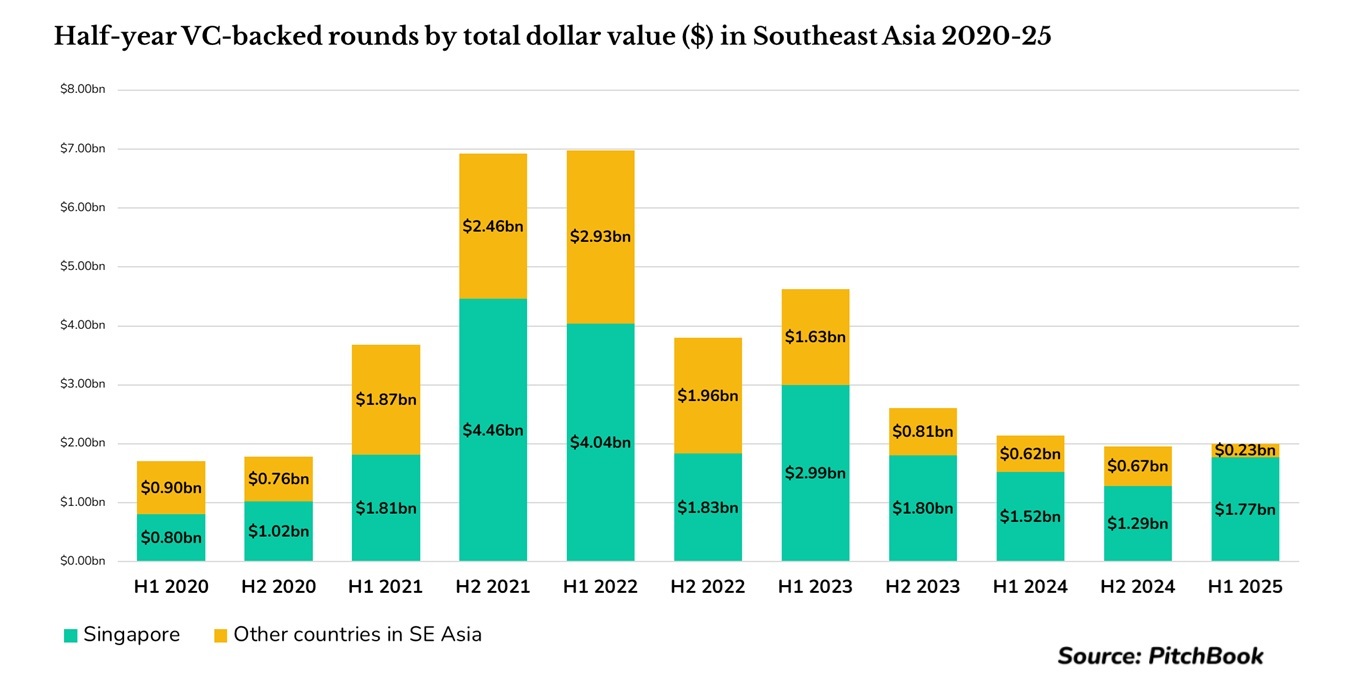

If any market in the region can be a model for this, it’s Singapore, which is now taking more and more of the early-stage funding allocated to the region.

Singapore has a population of only 6 million – just 2% of Indonesia’s and 5% of The Philippines. Because that consumer base is nowhere near large enough to launch a local version of Uber or Airbnb, Singapore’s startups have never concentrated on developing products just for the domestic market.

“That is why the Singaporean entrepreneurs focus on where the strengths are: engineering, technology companies, deep tech, maybe some AI; or companies that are tackling regional, if not global, problems from the start,” says Harnal. “Because the market size doesn’t exist domestically, you are forced to build more global companies.

“Indonesia is the exact opposite: the domestic market is so massive that you’re trying to focus on building consumer companies that tackle the domestic market. You’re not as interested in building B2B businesses because the consumption market is so big.”

There are other developments set to help recovery: a backlog of tech IPOs that are expected to revitalise local exchanges over the next three years, and recent regulatory changes in several markets intended to boost investment in those public markets. But Harnal is optimistic that a more global outlook will enable the region to bounce back.

“I do believe we’re going to see a lot more Southeast Asian entrepreneurs tackling global problems and building global companies right now,” he says. “I just think the idea of feeling domestic or regional is a limiting belief. What stops you from opening up that aperture and really building something that is much more global and much larger, that solves a problem that is transnational?”

“I would say the era of the big digital type of platform has gone now,” says Temphuwapat. In addition to the big incumbents in those sectors, international apps, most notably from China, are the ones making the biggest splash. But, he says, the region has plenty of entrepreneurs with the talent to look outwards.

“AI is good and Web3 is good, because we saw before five years ago that we have great developers, and three people with three laptops can launch something globally,” he adds. ”We hope to see more of those.”