The country has created 25,000 startups — but can it turn any of these into global champions? That is the next challenge for the government and investor community.

Japanese companies once dominated the global technology sector, with brands such as Sony with its Walkman and Playstation or Toyota with its “just in time” processing, creating new consumer device categories and production techniques.

In the 1980s and 90s, Japanese companies reaped high rewards for being innovative — in 1989, at the peak of Japan’s economic bubble, Japanese companies made up 32 or the world’s top 50 companies by market capitalisation. Today, after 30 “lost years” brought on by the bursting of Japan’s economic bubble, only Toyota is still in that top 50. Japan is desperately searching for ways to rekindle an entrepreneurial spirit in the country.

“Japan used to have a lot of global companies but a lot of them aren’t there anymore,” says Kenji Goho, chief financial officer of Whill, a 13-year-old, Tokyo-based startup making personal mobility devices such as electric AI-assisted wheelchairs. “We want to create one of Japan’s next truly global companies at Whill.”

Whill, which has raised more than $77m in funding, including financial backing from Toyota’s growth investment arm, Woven Capital, is one of a number of startups looking for a way to not just be big in Japan but big everywhere.

But, how exactly are global champions created? Can Japan create the next Nvidia or OpenAI? This is the question Japan’s politicians, entrepreneurs and investors are all now grappling with.

Creating a startup nation

Over the past three years, Japan has seen a steep rise in the number of startups and investors, thanks in part to the government’s five-year plan, launched in 2022, which set out an ambition for the country to create in five years 100,000 startups and 100 unicorns, or startups with a valuation of more than $1bn.

Tax incentives, visa reforms, and the creation of regional and global support hubs have been designed to make startup creation easier and to encourage big Japanese corporations to create corporate investment arms – both to support the local ecosystem and to help their parent corporations tap into new ideas to remain competitive.

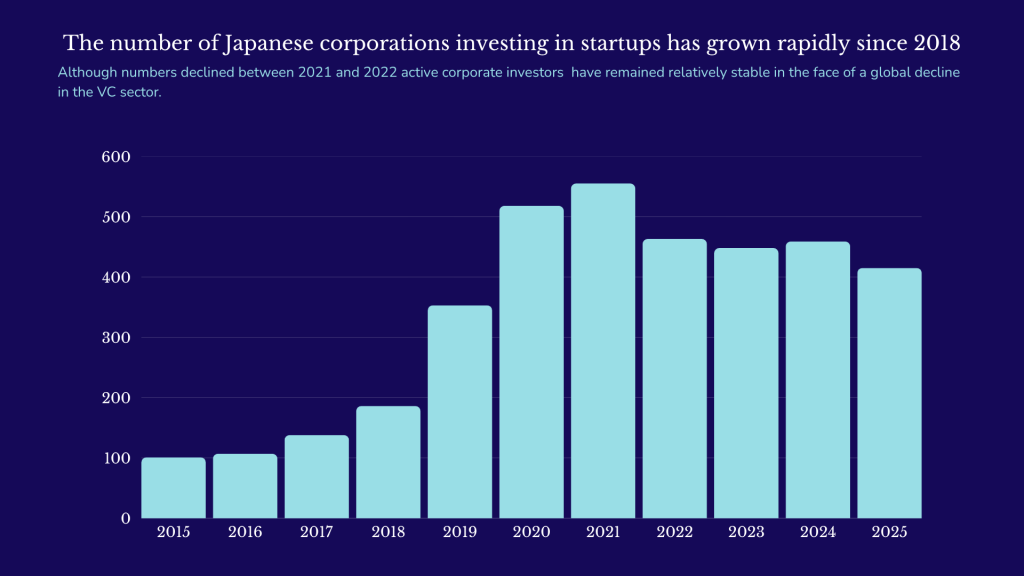

These programmes have had an impact. There are more than 400 Japanese corporations actively investing in startups, more than the double the number (185) in 2018, according to GCV figures.

Meanwhile, on the startup side, three years into the programme, there are now some 25,000 startups and around eight unicorns. Though some way short of the original plan, it has been a decent start.

Japan’s unicorns include Spiber, a company creating advance materials through microbial fermentation, and Preferred Networks, an AI company valued at more than $2bn, with investment from Toyota and robotics maker Fanuc. Sakana AI, which is developing efficient AI for edge devices, just raised $135m in a series B funding round backed by, among others, Mitsubishi UFJ Financial, Shikoku Electric Power and In-Q-Tel, the investment arm for the US defence sector.

“The Japanese startup and venture ecosystem was very nascent for many years and a lot of corporates would participate by being LPs in US based funds. But we’ve actually seen a resurgence of startups here in Japan,” says George Kellerman, founding managing director of Woven Capital.

The real problem, however, investors told GCV during the GCV Asia Congress last week, is that Japan has yet to build many companies with potential to grow globally.

This is the next challenge that Japan wants to crack.

“The focus is on scaling,” Hiroshi Ishikawa, director of innovation and startup promotion at Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, told the audience at the GCV Asia Congress during an opening fireside chat.

Stopping the micro-IPOs

New policies designed to encourage scaling include a recent change to the listing criteria on the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s Growth Market: companies must achieve at least a ¥10bn ($65m) market capitalisation after five years or they will be delisted. The idea is stop companies from going public via “micro-IPO”s or very small-scale stock market listings. Hundreds of these have taken place on Tokyo’s Growth Market over the past few years but these companies have usually failed to thrive after the listing.

“There is no late stage venture capital in Japan so startups have no option but go public after they reach around $1m in revenue. Unfortunately, most of the IPOs on the Tokyo Stock Exchange are micro-IPOs, around $30m-$50m. These end up in micro-stocks that go nowhere and eventually get delisted and the companies go bankrupt,” says Murat Aktihanoglu, managing partner at New York-based Remarkable Ventures.

Aktihanoglu is one of several foreign venture capitalists working with the Japanese government to persuade Japanese startups to list later and to go public on the New York Stock Exchange or Nasdaq instead.

“We are working with Japan’s government to go invest in startups that are about to go public on the Tokyo Stock Exchange and stop them, take them to the US market, introduce them to customers, help them raise money and eventually exit in the US market.”

Ishikawa told the GCV Asia Congress audience the government was also keen to see more acquisitions of startups as an alternative exit route to IPOs.

Continued support for foreign entrepreneurs and investors

Building an entrepreneurship culture in Japan has, in part, involved a policy of embracing the outside world. The country has historically seen very low rates of foreign immigration, but there has been a concerted effort to attract foreign entrepreneurs and investors — who can bring new ideas and skills as well as capital — into Japan.

“There are many foreign entrepreneurs coming to the Japanese market. There are people from US, Russia, China, India, Singapore, even Europeans. Not only the founders but all the engineers are coming and sending their resumes to our portfolio companies. Very high class, top class engineers,” says Ken Yasunaga, managing partner of Global Hands-On VC.

“There are many programmes that can help you receive a visa, find a place to live and get a bank account. There are a lot of good places that we can provide support. And I’m also the head of the global committee at the Japan Venture Capital Association. We are really promoting those entrepreneurs from all over the world,” Yasunaga says.

He says support for bringing foreign talent to Japan is likely to continue, despite some concern over the “Japan first” rhetoric from new prime minister, Sanae Takaichi.

In October, the country tightened the rules on foreign nationals obtaining a “business manager” residency visa, including increasing the capital investment requirements sixfold from ¥5m ($32,460) to ¥30m ($194,760). The move followed widespread concern that the visa rules were being misused by people creating “paper companies” used to obtain residency without genuine commercial activity.

Some venture capitalists told GCV that they felt the rule change was sending a “mixed signal” to foreign investors.

Yasunaga, however, says that the Japanese environment, overall, is likely to remain very welcoming.

“There is some noise that Japan wants to be Japan first, so they are a little bit hesitant to have more foreign people coming into the market. But it’s not anti-foreign,” he says.

Global hopes rest on deep tech

Prime minister Takaichi’s government has made clear its commitment to promoting Japan’s deep tech industries. Sectors such as robotics, semiconductors and nuclear fusion are seen as areas where Japan could create businesses capable of becoming global leaders.

Noriya Tarutani, head of the startup initiatives at Japan External Trade Organisation (Jetro), the Japanese trade promotion body, agrees: “I think our strengths are in deep tech — clean tech, climate tech and also physical AI. And because the Japanese startup ecosystem has been driven by corporates and CVCs, their interest is always in deep tech,” he says.

“The Japanese government continues to support startups. The new prime minister has said the same thing, she’s really interested in deep tech, in hardware, in nuclear fusion, and in climate and clean tech. We see no changes from the last prime minister to the present prime minister.”

An example of a potential global deep tech leader is EdgeCortix, a company developing fabless semiconductors for AI processing in edge environments such as factories, shops and remote locations. The Tokyo-based startup has raised some $110m to date, including a recent series B funding round led by TDK Ventures, the CVC arm of Japanese electronics maker TDK. It was the first time TDK Ventures had invested in a Japanese startup, despite being in operation since 2019 and racking up nearly 50 investments.

“We have a ‘king of the hill’ strategy on investments, where we will only invest in companies we believe can be global category leaders” says Nicolas Sauvage, founder and president of TDK Ventures. “EdgeCortix is one of the first Japanese startups we have seen that we believe can be the king of the hill in its field.”

Nuclear fusion is another area in which investment interest is growing. Tokyo-based Helical Fusion, for example, raised a $15m series A funding round this summer, helping speed its stellarator-based fusion reactor design, while Kyoto Fusioneering raised a $45.7m series C extension round in September, with investors including Kyocera, the high-tech ceramics and electronic components company, and JERA, the Japanese power company.

But the amounts raised by Japanese fusion companies are still an order of magnitude lower than those raised by US peers, points out Tomohito Shibata, partner at Japan Energy Fund. US-based Commonwealth Fusion Systems, for example, has raised nearly $3bn, including a $863m funding round in August.

Funding rounds of more than $100m are still relatively rare for Japanese startups.

See all the corporate-backed funding rounds for Japanese companies in the CVC Funding Round Database

Nevertheless, investors say Japan has solid fundamentals in deep tech, which may help it break through on a global scale.

“Japanese founders do not exaggerate but will tell you the truth,” says Aktihanoglu, noting that it is the one jurisdiction in which investors don’t have to take entrepreneurs’ promises with a pinch of salt. “They under promise and over deliver.”

Julian Mialaret, operating partner at Eurazeo, a climate investor who has explored the Japanese startup ecosystem for a number of years, says the focus on deep tech is a positive. “Japan is finally coming out of that awkward adolescent phase where it is wondering which way to go. It knows it is good at deep tech,” he says.

The big question remains, however, whether this will be enough to put Japanese industry back on the global map.

Maija Palmer

Maija Palmer is editor of Global Venturing and puts together the weekly email newsletter (sign up here for free).